Plants grow.

Universal, no brainer, a truism, a chiasma of sorts, redundant intrinsically, a game – or so you think until you possess a garden of your own. Whether by accident, coincident or design, when it’s your turn to worry along your land, your crops, what do you do? Can you really trust the late, unruly beans, can it be such a snap to reach peak courgette and what of the truant refuseniks, the peas? Does seed imitate season?

Planning a combination of immersion and observation, I was ready to put such a redundancy to the test.

We were new to Bath, new to England, and we were skint as we pushed restart. Grocery shopping was painful after the ease of perusing farmers markets when living abroad. A return to homegrown would secure our health and cushion our finances. Plus, our own Eden seemed like a chance to meet people and burrow under the skin of the place.

Was I entirely clueless? No, Grandfather Gustaf rented an allotment right here in Bath 40-odd years ago, and I wondered if his site was still in play. All I could recall was a sumptuous pear tree and rows of garlic and leeks. So by tracing the canal towpath from Sydney Gardens, dropping along a cascade of locks to the last historic turn where the water merges with the Avon River at Widcombe, I scouted his old spot, Abbey View. Sunny and warm that day, plenty of plots had potential, and I investigated how to register.

The plan to garden made sense. I now lived five minutes from the countryside in a pretty, pastoral city with all the mod-cons. I was over forty, injured and no longer enamoured by the grind of endurance sports. And I had time to dispose on the seasons.

The preconditions to plot rental were proof of residency and council tax during a simple application process. Spot 16A at Abbey View was proposed.

No doubt 16A was a great choice because it was a wreck: abundant grass, brambles, carpet, collapsed decking, neglect and nettles, stumps and unstable ground. A grand fig, a few damsons and a superb location were its saving graces.

Abbey View is a crescent of steep garden terraces cupped above the rail, road and river corridor nourishing the elegant, dishy city of Bath. This natural amphitheatre of ground with its aspect to the great southwest directs clips of conversations to your ears, whether passing human or swooping bird. The close acoustics create a feeling that what you’re experiencing is layers of a toy city, the stop-motion dance of traffic and to-and-fro of rapid delivery Sims, a soft play of light on the city’s almond surface poured onto the hills, in the mid-ground the many churches built by generations of pilgrims to the spa city, underfoot the thick Somerset mix of turf and mud, the brine of the sea suspended on the horizon, and inside my skin considerations on timing, tasks and plans.

Yes, the backdrop’s real – relaxing, stunning and beautiful to look at, with shovel or fork in hand, giving every ounce of being and strength to the basics: moving dirt and fighting grass.

And what a relief, too: no logins, notifications or screens here. Let’s be honest, I’m not a fanatic homesteader starring in a championship channel for fruit and veg. Nor am I prepping for World War Five. No, I’m chasing solitude and independence, a legitimate excuse to peel away from home and to gain a sense of accomplishment I might not necessarily have, then combining that objective with a test to see if a slow calendar can culminate in the crunchy and edible.

Five years later, the challenge has knocked me about and changed my perspectives of what’s fun or doable.

With just a shovel that first season and a few words of advice from my father 5,000 miles away, I set to and cracked on, tugging out the stubborn white roots of weeds and grasses, then re-establishing the borders. Winging it in every way, I shamelessly scavenged for lumber and free compost, morphing into him in the process, for he never minded looking like a tramp when he wasn’t flaunting his oil and gas ties at the office.

To learn was to observe the adjoining plots, some in disarray, others precise, each decorating the steep bank studded with fruit trees, huts, trellises and greenhouses. Around me, a community of gardeners beavered away, and it became apparent that I had a lot to absorb about ecology, pest control and what crops worked.

Charles warned me to avoid sweet roots and Michelle said she still didn’t know how to grow proper raspberries. Pete said just muck in.

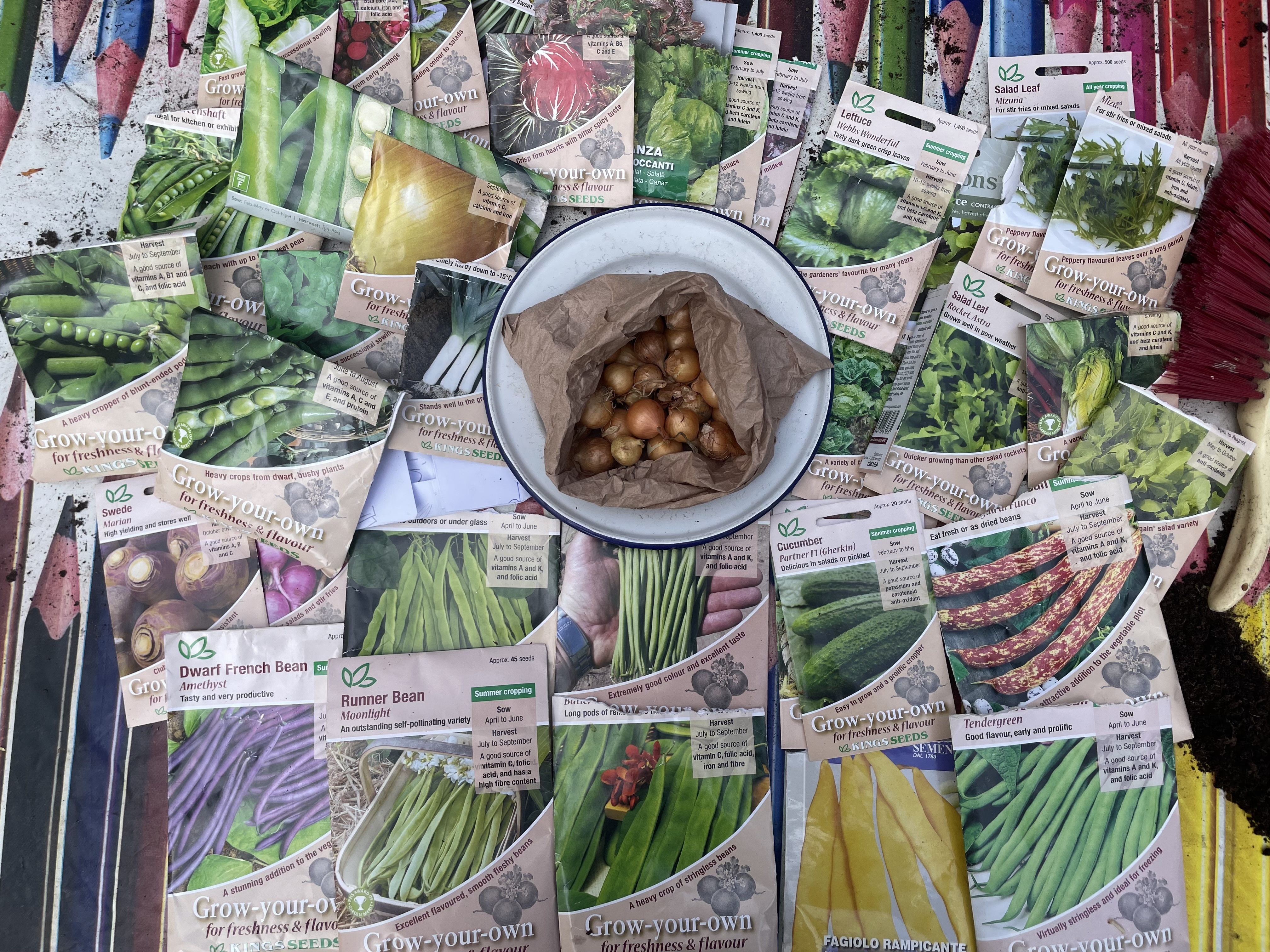

My idea was copious salads, beans and anything else that reminded me of the markets of Central Europe – produce loose and wonky, attractive and magnificent.

I planned for a few investments in year zero: improve the soil now and cover till planting. I biked out weekends to the Trading Hut run by the city’s allotment association, ostensibly for at-cost tarp and seeds. Bike panniers overfilled with supplies: chicken manure, blood and bone meal, seaweed concentrate, slug pellets, seed trays and whatever else I could tote or bungee. I hankered to attack – or at a minimum sort out what grew and how.

Nothing made sense at first. Were the manuals right? Did a good crop boil down to soil temperature and microbes? And why was I standing mid-week in the gardening annex of Home Base inadvertently shopping for deals on trees or trowels? Should I devote a step to germination at home and then transplant seedlings when it warmed outdoors? Or did I have the courage to sow directly into the dirt? Or should I do both as an insurance policy from the attrition of pests and disease?

Incrementally I could chart wins and losses as the season began in earnest.

Wins

- Salads and leaves – hardy and excellent

- Onions and shallots – sweet as fruit

- Brassicas – prone to error but divine

- Potatoes – sensitive but tasty

- Beans – late to start and buckets of fun

- Cucumbers – adore the junky sun of a stump

- Courgettes and squash – delish little fish

Losses

- Carrots and corn – bait for badgers

- Radishes and turnips – hit or miss

- Tomatoes, okra, chilis or aubergine – useless outdoors

It seemed like a case of beginner’s luck, and as a novice, I fussed over the garden, weeding weekly, tying and propping up plants, watering with the slightest dip in rainfall, spraying for black fly and other pests, pruning away blight or scissoring away aggressive grass. New to nature, I forced everything into neat rows and handpicked leaf by leaf.

Plans Grow.

Over time, I came to understand the garden as a subtle ecosystem where you can plant for more than one season, intercrop or cook your own compost, where you can manage a riot of growth and ripeness and decay, where you can even plan for early crops and late crops, allowing space for you to take off, at your peril, on August holidays.

The real bonanza was dotted around the borders of Abbey View, where I discovered unclaimed plums, pears, apples and quince in late summer and early autumn – regarded as community property on a first come first serve basis – with the caveat, it’s a shame to waste. That suited me perfectly as I was struggling to make ends meet, and my frugal cellar subsequently overflowed with trays of scrumped fruit, sacks of potato, squash or dried beans, rows of jam and relish, enough to span the gaps in budget and diet (enough sadly to entice the rats out of the drains in another incident).

O, I was in heaven alright and savouring the role of being steward of my domain. I especially liked the warming organic effect it had on my thinking and writing. Page and garden appeared to be a match for an individual who takes fifteen years or more to complete an essay or story. I recognised and appreciated the slow, independent flow of nature, a kind of soft, messy mastery of five rectangles that had little to do with agricultural concerns like profit, margin, or scalability, even if there was an associated violence place of disturbing the ground and extracting its riches.

Yes, gardening is politics, and sovereignty is found in belly, table and story, in the knowledge that you have agency, an epiphany that you can trust the earthy fundamentals of growth, creativity and expression, of light, warmth and season. There is comfort in the small mutable steps, a repeatable pattern where you can shape real life, far from the externalities of doom scrolling or tyranny, streaming or celebrity, where you can witness and enjoy results in a purposeful state of unaware.

Imagine reading trees in winter and imagine how they blossom and spread in the years ahead. Imagine standing at the border of your patch in early spring and mapping out the geometry of your living larder, imagine filling your beds and pitches with the courage of your belief. Imagine sowing the earth with bean, tuber and seed in expectation of a spurt of life that gives your garden voice, that creates space and converses with and through you in the language of plants. Imagine ditching alerts and notifications and returning to planning on the old timeline of if not this year, then next. Imagine bending at your own speed to tend your plot on the steep slopes of Abbey View.

Yes, there’s something big and soulful in gardening, an ineffable, ungraspable but relatable tonic. When faced with roadblocks or projects beyond our motivation or ken, the garden presents a step-by-step approach to arrive at your goal taken from the core of management. Whether formalised as Gant chart, PSI table or whiteboard, the project sends us to the basics of a calendar, alarm and forecast, a confidence in our human acumen and approach to ingredients that may well lead to the pulchritude of harvested greens and reds. Yes, killing time in the garden we can be free from keystroke, scroll and the thousands of miles and hours we track on screen, free far from the ethos that you’re only as good as your room: if you’re blurry and buzzing, you’re out, just a piece of furniture.

The advantages of the deliberate pause and procrastination of the garden should outweigh all that lingo of modern management. Our families (troops/mobs) can join us with tea and sandwiches, or we can stop at the Pump House for cheap ice creams and teas. We can try not to hurt ourselves in the interval, or we can hurt ourselves anyway. We can raid the currants and gooseberries on the right occasion for summer pudding, or we can drive the cold and mud into our bones and skin in a great battle against the elements. We can tote our remote speaker and serenade the world with beats while we drink tea and eat two Twix as we recharge, or we can paint a shed in linseed or acrylic and dress as junky as we want (a shabby gent’s wardrobe of holey green tweed or corduroy accompanied by a twinkling mindset of frugality, scavenging, making do and invention topped with a sweat-stained hat). We can smoke, think, journal and observe the passers-by across the murky canal water at the bottom of Abbey View, or we can look into the horizon of Welsh storms and note the incoming bands of rain touching Round Hill, then Lansdown, then imminent above us at Alexander Park, sending us to our shed for rainproofs. We can pick out the green nest of sycamores at the Circus and the emerald ribbons of Bath’s parks, all of it fronted by the stately abbey and the toffee facades of Bath central, putting ourselves irrevocably in time and place, our feet placed in the mud and grass of our own slice of hill, relieved that we are here.

What’s more, we reliably return time and again for exactly the same experience, meanwhile running the risk it might just be ruined, for the bounty, delight, and reverie in the landscape can be short-lived and quixotic. Who’s to say badgers, wood pigeons, deer or rodents won’t visit and gobble up the tenderest of crops. Or wind or hail or rust or insects? Will it be too hot, too cold, too wet or just right?

Setbacks, true, but just part of a plan that accommodates for failure and death, for no one expects all the seedlings to prosper in the violence of the garden in the struggle for nutrients and light culminating in the injustice of harvest – when at its peak hundreds of glorious civilian peas or succulent beans are tossed cavalierly into a bucket and carted away to be eaten alive, when clusters of berries are boxed and later asphyxiated in puddings, pies and sugar, when platoons of courgette soldiers are captured, casualties to be julienned into a hot pan, when we displace tubers from their burrows and jolly them into a jute sack for the pots and ovens later, when we snip away colonies of lettuce and greens and relocate entire settlements into the bowels of the salad spinner, when after the gleaners and the frost, we cover our wasted crops with plastic sheeting and end the season?

Let’s breath easy about Arcadia and acknowledge a past that impacts the today. In a locale like Bath, violence is coded into nearly every view, the price of its avenues, buildings, estates and gardens financed by reprehensible slave traders like Pulteney and Beckford, now fairly targets under the lens of critical race theory that supplies a rewrite of the city’s official books.

So why all this hyperbole and personification now? Why advocate or allocate such weird language to a garden? Why make a delight so suddenly corrupt and freighted with so much meaning? Precisely because of the mental space and unstructured play that a garden allows, a reminder that parameters like time and temperature, light and water, can affect change in your thought and consciousness, that you can reclaim agency from digital through action, care, labour and the dirtiness of one’s hands, and then input, if you like, that same sunny grit into your calendar of profession and person.

Links