Willy Reed’s motorcade sighed along the thoroughfare. Posters of what he supposed to be his face decorated the way. The man on the posters looked nothing like him, for he had been sketched according to the deep, smoothness of his tone; while he was wan and drawn, the Willy Reed in the posters resembled a movie star. He was anonymity not fame, the voice.

Poles had congregated along the streets to see this extraordinary and unlikely hero who had materialized from the ether, a supernatural being made of American jazz. His fans clapped and waved. Others steadied homemade placards, sketched with the outlines of horns and pianos and painted with jazz’s best and brightest names: Dizzie, Monk, Miles, Duke.

The carp-like mayor pointed out the city’s attractions from the convoy: the smelly abattoir, the sausage factory, the textile mills that were the town’s fortune, the stadium next to the bus terminal cloaked in diesel particles, the gray city hall across the street from the sole radio station, and a forlorn department store in the town’s main square. They avoided the military base, the set of contorted towers that were a broadcast jamming station, the airfield and the ball-bearing plant.

“Good ground for jazz,” he thought.

A sensitive moment passed when they came to the spot where saboteurs had revolted in the spring of 1956. Willy nodded bleakly at the site of the insurrection.

Willy remembered that he was forgetting to remember when he should be forgetting outright. It was a tricky lesson, negotiating what reality, what past and present, meant here in communist Poland.

Willy waved politely, acknowledged everyone. He smiled. He tipped his hat and bowed.

“Why thank you, thank you for listening!”

He was shocked. He was more popular than Kennedy. Groupies had besieged his hotel but he wasn’t about to tell that to Emma, his wife. His minders in Munich and Washington would want to know. They would be pleased. Jazz was winning the war.

Willy Reed had a troubling interview in Warsaw towards the end of the tour. He listened after deflecting the pointed and embarrassingly incisive questions of a Mr. Ryszard Kapuscinski about the social conditions of blacks in America. It was unseemly to talk about poverty or inequality. Everyone had to believe in the lie. In that department, the Reds were equal.

“Why do white Americans love jazz?” asked Kapuscinski in his flawless, accent-cleansed English.

Willy knew but he pretended not to know as the questions came hard and fast.

“Sexual innuendo? Individualism? Cool? Too cool for its own good? Because there’s the Beatles and the Stones are the coolest?”

“They aren’t just listening to black music, but remaking it, like Elvis,” said Ryszard, rushing for an insight that would convince Willy that he was a friend.

Willy Reed was immune.

“The music guides me,” he said. “I can’t guide the music.”

Yes, Willy Reed blew tunes all over the world. How he did it was a trade secret. It was all up to the voice.

He had been warned beforehand: be cautious.

But of who and what?

Of clever reporters like Ryszard who seemed to know it all?

Or the scruffy Polish musicians who urged upon him ingenious records made of flimsy X-ray film?

He laughed at his growing stack of morbid roentgens pressed into albums. The communists couldn’t possibly be prepared for covert solutions to censorship like this. And what was the harm in smuggling those recordings west, when he loved rebellion like he loved music?

He wanted more.

The public address speakers were mounted in innumerable places. The whole country was wired for sound, for instructions and patriotic marches, no more so than in Warsaw’s main department store.

The escalators were out of order. Willy took the zinc-coated elevator to find the music department on the top floor. He was stunned by the choice behind the counter: the doctrine of communist brotherhood had brought Balkan and Caucasian jazz to Poland.

The clerk became irritable.

The smiling pig wanted to hear everything.

She begrudged every request and scratched from track to track, furiously operating the record player.

Only when Willy barged behind the counter to save the vinyl, did she retreat.

In a corner she poured her anger into an ersatz coffee and a black cigarette.

Willy admired how people went to work yet got paid for not working in Poland, but soon he forgot about these inconsistencies as he heard the unfamiliar compositions and modes: duduk mixed with a maqam-tuned piano or a trio of kavala, accordion and tombok. Joy stormed through his heart at the credit he would receive for such discoveries.

Later, Willy struggled to pay.

The clerk cringed: the foreigner needed to change money, which involved a detour to the foreign exchange safe in the basement. Then a manager had to be requested to open the box containing the coupons that he could exchange for his dollars and then zloty.

Why did they make it so hard, he wondered on the way back to his Warsaw hotel, his shoulders tipping into the bags of records.

He found his short-wave radio in its nylon case on the bed. He scanned the channels. The reception was dirt. A crackling something. Then at last his voice, his show, tinny, prerecorded, with none of the verve of a live transmission. The chord changes were hardly there

He bristled when he realized the programmers had amended the song list. Where was the hot angry jazz poet Gil?

Fearful, the editors had been too sharp. If Willy deviated, the memos would come. The programming honchos didn’t love jazz in the least. But they collaborated to make glamour in the studio, Willy hunched up in front of the microphone, the god-like, knightly tenor in his throat, holed up like an owl.

Jazz reinvented itself was what he usually explained—no need to get alarmed.

The administrative interference made him backpedal about getting back to Washington. Anyway, they’d have to wait. Willy had agreed to meet Emma in Barcelona after the Polish tour. It wasn’t just his wife’s idea: he was curious about the Catalan antenna farm that pushed his voice from the Mediterranean to Poland and beyond.

At his farewell party at the embassy, a large Polish official cuffed him on the arm and pulled him aside.

“Comrade Reed, jazz has made us broke!”

Willy laughed with the jocular official, his humor covering the seriousness of what he had to say. “Stopping music is like stopping energy, the energy that makes us grow.” Willy kneaded his own hands.

“We’re fans, Willy. We dance. But don’t you realize? Whole orchestras are dedicated to drowning you out! We’ve made double-headed turntables and Babel-like machines to stop you. But you won’t stop. So keep up the good work. Wouldn’t you know, my enemy’s enemy is my friend.”

Willy was aware of the jamming too and standing before him was the broad, cordial enemy who America sought to ruin.

“Do you know what jazz is?” he asked. “Alive!”

The official bothered to argue with him.

“No, Willy. Jazz is an alien, devouring our planet and making something new. Disney inspired Eisenstein and you’re next.”

Willy Reed smuggled his cargo of recordings from Poland to the West. He would be debriefed at some point and his mind brimmed with notes and. Much of what he’d seen in Poland seemed like a facsimile, everything second- or third-rate, a knock-off, prone to falling apart. It was refreshing somehow, a world without capitalism, with so many loopholes and shortcuts, gothic and otherworldly, old and new simultaneously, where he could be a misanthrope all he wanted.

The stop in Zurich to change trains gave him the creeps. Was it the Swiss?

He pulled up the collar of his coat. He dunked his croissant into his coffee in the haupbahnhof café. He glanced at the Trib and waited for the blower to Barca. Willy felt like espionage.

Skirting Lake Geneva, a group of Swiss hopheads jazzed up in the compartment. They were cavalier and untouchable. Their behavior went against his astringent ways, but he respected that. He wouldn’t interrupt musicians in their rites backstage either.

Jazz was real toil; that’s why it sang: let live, baby, let live!

They had agreed to spend a night in Barcelona. Emma met him at Hostel Del Norte. On a side street, dark inside, they had a tiny suite. Willy thought the kitchen extraneous but Emma was insistent. She needed her teas.

“So?” Emma asked. “How were the grannies in Poland?” She was in a lairy mood, jealous, neglected.

She was pragmatic, too. She wanted to know he loved her, especially when he had been carousing instead of home. She worried about the girls being too sweet, fast and loose, in a world of clubs, musicians, promoters, and the incestuous radio.

It was hard to believe he could be so popular. She snickered at the idea of Willy being a hero, the guy with the huge record collection. But he was chivalrous and old-fashioned yet firmly open to whatever people had to sing or play. He didn’t really judge. She liked that because she usually issued hard verdicts.

“Like to go out? A little later, hmm?” He could make out her prim porcelain body under her clothes.

He understood her perfectly. She didn’t want to go out at all. Not without a cuddle on the mattress they affectionately called the office.

The plaza had a MIG perched in its center. Willy had forgotten how much Barca loved its rebel friends in Latin America. He appreciated the graffiti scrawled on its wings. “Die Yankee Capitalist Pigs.”

Emma pointed the way to the restaurant along one edge of the plaza. They sat down and soon were served.

“Spain’s a big country,” he said.

“Don’t start, Willy. Playa de Pals sounds great to me.” She was lazy. It was Willy who always wanted to go somewhere, anywhere. “This isn’t one of your secret jazz islands, is it?”

He frowned. The last trip had been rough. She shouldn’t have come to Jamaica for his research on Calypso. The obeahmen had frightened them both. This time he just wanted to drink the utilitarian red on the table.

“Come on, Spain’s civilized,” he said, making room for the plates of fried baby octopus, jamon, pig’s ear, lambs’ kidneys, a crock of steamed clams and pork, flambéed shrimp, then a grilled fish.

Emma was unrestrained. Food like this they couldn’t find in America, even along Chesapeake Bay. Emma dreamed of a culinary boom at home. Volubly, she scarfed up the platas, then ordered the honey pudding and asked Willy for a cigarette. He’d kept pace too.

“Reminds me of Seafood Heaven in Harlem. Great fried basket of fish and greens with a hardly room for a man to eat,” he said, gaining the attention of a waiter for an aperitif.

“Swell, Willy,” she said. She had to plan how to divert him from going to a jazz club. He was incorrigible, but on this evening it wasn’t too hard. Willy knew when best to play by the rules and the couple picked their way back to their hotel.

Emma was feeling a little wild after the Cava. She kneeled on a dark corner and held him in her gloves, then her mouth.

Their departure came after a very late lunch.

The apartment at Playa de Pals was right on the beach, so the brochure promised.

Damaged by alcohol yet restored from hours sealed together in the cramped room, Emma and Willy were functioning smoothly.

They were to look for the driver at the railway station in Pals.

An older man collected them as the sun fell behind the mass of Spain.

“Señor y Señores Reed?”

They rode in a charmingly beat-up Citroën. Willy was scrunched in the back and Emma asked, “What’s your occupation, Señor?”

Lifting his red hat, he said, “I was chief of police here for fourteen years. But now I’m a public attorney in Barcelona.”

“Nice to meet you!” Willy said, jokily, remembering some of his most serious childhood pranks, of which the zombie had been the clincher.

They veered along the twisting road.

“What’s your biggest case?” Willy liked asking basic, obvious questions to get people talking.

“Murder,” the attorney said matter of factly, “Family business, a young girl raped and killed by her father down by the beach.”

“Dead bodies lie all across Europe,” he replied. “Makes it rich and appealing as a target audience. Jazz wakes up all those corpses, limbos them back to life with dead men’s music.”

Emma and the attorney studied him quizzically.

What was he on about?

The car strained.

The house was down a dark lane of twisted cedars and rosemary shrubs. The headlights beamed down the hill, steep and turning abruptly.

They walked down the last stretch of rocks and gravel.

The room was ready. But the cabinets were taped shut—cut crystal glasses, trinkets and different herbal alcohols, mostly from Socialist states.

“Sherry,” exclaimed Emma at the bottle on the table. “How cute! They must think we’re English! I love Spain for its mild alcoholic drinks.”

“But it’s sweet,” he said, tapping the label.

Burlesque, red curtains framed the sliding door onto the veranda. Gauze nestled behind the heavier velvet. Outside, twinkling red stars blinked in intervals. Fixed in the sky were the silhouettes of antennas, scores of them, humming into the night as if on a stage.

Willy and Emma strolled to the beach. They twisted through the branches of a fig tree and crossed the vineyard. The air tasted like oregano, rosemary, and salt. With the aid of a flashlight, Willy crossed through the rocks for a swim. A boat came out onto the bay.

“Going to cancel our tickets home, it’s so perfect. Could do my show here, I bet.” Wet, he dodged a mosquito.

“We’re going to love this,” Emma said. A star dropped across the periphery into the net of red antenna lights. Lightening jumped in the distance, then settled over the antenna, gobbled up.

“That was strange,” she said.

Then the light pulsated again, danced in the structures, emitted a warbling tone like a Theremin.

“What you make of that?” he asked.

Emma didn’t know. It frightened her, the shape of an odalisque beckoning from the light array.

They had the run of the beach that night but they retired, troubled by unease. It was too dark. Where were they?

Emma slept erratically. Her stomach hurt. She blamed the cactus fruits they had peeled and eaten. The bedside lamp glowing on the wall, masked with a wet cloth, she made flashcards.

She noticed the macramé framed on the walls had a goofy touch: poinsettias, a mountain stream, a still life of fruit, a winter scene. Emma also made a list: candles, mosquito coils, toilet paper.

Later, they both awoke.

“Someone moved the shutters,” she declared.

“Do you like being afraid, Emma?” he asked to allay her sense of foreboding.

The mood was anxious. The sea and wind were noisy.

A squall?

“Hush! Hear that singing?”

“More like a siren,” Willy said. “Late night maintenance at the radio.”

That’s what he explained as they hugged one another under the blankets, cold and spooked, their bodies clenched together.

He remembered one way to survive, doing pushups at the rough terminal in downtown Washington as a kid, keeping himself awake, waiting for the bus after a night chasing jazz.

“Will we be able to stay here?” she asked him. “Or will we go insane?”

With first light, everything was revealed to be what it was: heaven.

Willy Reed left his cowboy coffee to cool.

The attorney already was spraying the grapes.

It was absurd that the garden path led to a door, weathered and framed with palm fronds jammed into the fence, that opened awkwardly onto a cement dock among the rocks. The bleached sign over it was illegible. It was theatrical to Willy. No one was there this early so he slid his long naked white body into the bay.

Willy favored the backstroke. He looked at the big house, the top floors incomplete. How lucky he was, mostly his own boss.

He woke Emma by rubbing her nose and feet, made tea, sat in the sun and assembled a rudimentary breakfast. There were no other guests. He lit his first cigarette. He was that in control and Spain made him feel that good.

From the attorney they learned that the grocer would come in a van later. The shop was on somewhere on top of the hill. The big deep bay was the program.

***

The sea sounded along the coast and the brush cut their legs. It some places it reached overhead. The path repeated, rising and falling through the rocky hinterland. It was slippery, too. They sidetracked to look at a chapel, just stone and tile. A large patch of underbush had burned and Emma posed in a dead shrub, Willy taking a photograph of his Amazon among the black spears that poked from the black ground.

Willy dangled from a cork tree with a big zero painted on it.

They tramped on.

“Where are those damn towers?” Emma asked. Her feet hurt. She adjusted her scarf that she had tied like a hood.

“Must be the long way,” he guessed. Were the towers just a feat of his imagination? Distances were deceiving without a car.

“Hungry?” she asked.

That was a command not a question. He stopped and dispensed some figs and peanuts from his bag, then they soldiered on. At last they passed the grounds of a golf course, the golfers shouts marshalling through the quietude. Then came a parking lot.

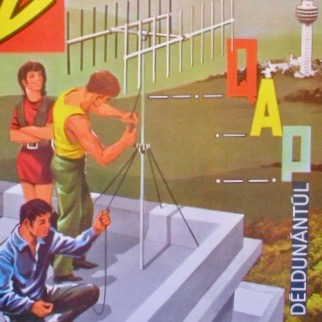

The towers rose from the point. They were a spectacle of red and white paint, girders, cement and wire membrane—wishbones rising from the rock and ending in air. The station was composed of four large clusters of antenna, four speakers in effect, facing the Mediterranean. Each group of antenna supported a thick curtain of wires, dipoles, the very living, breathing, electric surface from which radio waves were born.

“Emma, welcome to one million watts of jazz. So hot, it could cook you like a microwave.”

It was hard to imagine that the footprint of his voice started here, marched from Hungary to Siberia, walked through the Soviet’s walls.

“This is your giant sax, huh?” she said. She expected something grander than these floppy sails. She pressed her face to the chain link fence surrounding the complex.

Willy’s show wasn’t broadcast back home. By some quirk of the law, it was illegal for the American government to broadcast its own propaganda to Americans.

“No one knows who you are or what you do, Willy. What’s the point if the home crowd isn’t in the know?” She guessed he was happy with it that way. He was modest and let others receive the praise.

“Yes, but in Poland they do,” he said, his head hanging in disappointment. “Anticlimactic, huh?”

He was fixed to the spot. It was a fabulous instrument. His hands swept the sky. “Up to this point, we can control everything.”

The radio had an advantage for a few hours each day when a gap in the atmosphere allowed them to beam under the Soviets’ interference.

The wind ran through the wires like voices.

“Isn’t our place over there?” she asked. He was useless. They’d sketched a massive circle, made a record of their walk.

“Let’s have a bite to eat and then we’ll say hello, yeah?”

“Where, Willy?” He could be so impractical.

“The town’s just ahead.”

They choose the place with the dirtiest floor—that was the sign.

Shells, rice, bones, cigarette butts, broken glass, and dirty napkins—the food was that good.

They drank glasses of tempranillo and washed down the steady, coarse foods, pulpo gallego being their favorite. Inebriated, they found a nicer bar with soft leather chairs. Clearly, they were radio people. They ordered amaretto and smoked cigarillos. Willy blew off the idea of visiting the station manager, Rick.

Later, sufficiently whole, they found a more comfortable plaza next to a stern brown church. Pools of white and red wax had stained the flagstones.

“That’s Mary and Jesus’ blood,” Emma said and he nodded.

Spain was weird.

They stopped to admire two attractive crumbling stone towers. Young boys were blowing coronets, making strange martial chops.

Nice. A super arrangement.

The sky soured. The sea darkened to an indelible black. Then the two merged together as the light ebbed over the mountainous coast. The clouds were scarce, low, yet fog had collected out at sea.

The way back to the house was much easier despite the wind.

Both smoked along the water’s edge. Emma wished she’d brought a sweater against the cold. She huddled in the break of Willy’s body.

They walked past the antenna masts, striped red and white, humming with power. The trusses were laced with ladders and catwalks. Very ingenious. The lights beat steadily in the frames like the heartbeats of birds.

“Couldn’t have built a mirror more perfect,” he said admiring the Gulf of Roses. “You bounce the signal off the water.”

Wind moved through the pines and amplified the quick, surging dissonance of the sea. Lightning sparkled at one corner of the bay and then moved quickly to nest in the towers.

“Look, like last night!”

It had no form.

“Will?” she gulped. “What is it?”

It was whatever they wanted it to be.

“Stalin?” he guessed. The electric display looked like a gargoyle on its throne.

“Quick, a photograph!” She wanted to document it, apprehend it. Emma juggled the camera and snapped at the blue plasma glowing in the darkness.

“Catch it?” he asked.

The shape hovered in the towers, crawled feebly in the wires, swayed, climbed to the very top, hovered then leapt, descending in a shower of sparks, sliding through the electric snow and then vanished into the ground, leaving a dash of smoke in the air.

Was it human?

Emma screamed and Willy jumped.

“Where is it?” She blubbered. “Where?”

“Beamed back to the Soviet Union,” he said, hooting at the thought of paranormal war. Had the communists sent the dancing ghost of Uncle Jo to defeat Willy’s jazz?

Despite his disdain, he was rattled.

Willy reached for Emma and gave her a hug. They were imagining things. Surely it was an electric phenomenon, hardly unusual when broadcasting in gigawatts.

They forged home. Willy felt the breath of the fog at his back. It was mad: a ghost versus the most powerful voice in the world.

“Wait until the spooks find out.” He opened the door to their quarters in the big silent house.

From the veranda the towers danced in the distance. Bebop. Twist. Boogaloo. Limbo. Boogie. It was quite a show.

Dumbfounded, Willy was inspired, puzzled, worried and still a little drunk. He concluded to lay off the firewater, the tasty aguardente. At least the episode made their holiday romantic and they were charged with that intense thrill when they went to bed.

The rising sun dazzling over the sea blinded Willy’s eyes.

He liked getting up early when he was on vacation and he didn’t hesitate to stump down to the vineyard. A litany of questions had tumbled through his mind all night.

Resting against a rock wall, the attorney denied ever having said anything about a ghost.

“There are many rumors in the village about the radio. Some say a listening station; others a submarine base. Believe what you will.”

Willy left the attorney to his grapes, which looked overripe, and went for a dip. He paddled away from the shore. Treading water, he studied the array of towers. A tanker was anchored offshore and pumping fuel into the base’s fuel tank for the generators.

Of course, the best cove was right at the foot of the towers, and swimming was discouraged there. Nothing indicated a dock or bay for submarines.

He swum lethargically.

When he got out, chilled, he was surprised to find a pyramid of oranges next to his espadrilles. Willy Reed wondered if he should eat them, if there were poisoned, or worse, radioactive.

The gate buzzed open. The road was newly paved. The landscaping was immaculate thanks to the efforts of the well-paid Spanish ground staff. Cars were parked in neat rows next to planters of agave.

“Willy, isn’t that the attorney’s car?” she asked. “Wasn’t he leaving today?”

“Just another jalopy,” he said, sweeping her toward the main building made of stone, aluminum framing and glass. A flagpole tapped in the wind. A water cistern rose beside the building. A lone palm bent to one side.

The door eased behind them. A cute robot assembled from transmitter parts—a walking figure with a circular sweep of electric hair and bolts of electricity for hands—guarded the lobby, smiled upon by a framed portrait of Kennedy.

The corridor was unnaturally wide, the floor white linoleum, and several murals of the transmission footprints and a map of Eurasia decorated the walls. There was no mistake where all this energy was going. A water cooler glugged outside the control room while the entire right side of the building hummed sweetly.

“The transmitters,” he said.

At the end of the hall they introduced themselves to Rick, the brawny station manager. He stood up from his dark desk, pushed back his plastic and stainless steel chair and leaned against the wood paneling, the blinds drawn tightly against the glare. He already knew everything from the Spanish staff.

“Saw something out there last night, huh?” Rick said as a way of greeting the imminent DJ, Willy Reed.

“Pair of loons, that’s us.” Willy was ready to admit it: they were nuts.

“Get our fair share.” Rick laughed crookedly. He was too red and pickled for his age. “Want to look round? See if we can’t get to the bottom of the big mystery?” He wiggled his fingers with menace.

“Sure,” said Emma. She’d never been interested in Willy’s work but she was endeared to the idea of a ghost, maybe a little girl. Emma couldn’t wait to develop the film.

Rick began by showing them the control room, all the components trimmed in blue. Banks of switches and blowers kept the transmitters cool.

“The Continental delivers 250,000 watts,” he said. “A quarter of our signal.”

They peeked in a cabinet holding the head-like vacuum tubes and all the precautionary gadgets designed to stop them from burning up. It was acrid like high-tension power and deionized water.

Rick cradling an old vacuum. “Spark plugs for that jazz we’re driving to Moscow.”

Willy chuckled.

They made steady progress through the complex. They looked at more transmitters. They observed the supply store and workshops. The physical plant. The motor pool. The gas pump for the station’s fleet of cars.

Emma yawned. It was very benign.

The manager and his guests strolled under the antennas whispering with the breeze. Emma took off her shoes and enjoyed the dry sand. Lizards darted through the grass and egrets were stalking the bounty.

“Anything abnormal last night?” asked Willy.

“Nope, checked the logs. What time you see whatever it was you saw?” Rick looked longingly back at the office. Kooks.

“Around eleven, I guess. We’d been in town, then came down to admire the towers before going home.”

“It was a girl, a young girl. She looked awfully sad,” added Emma. “She scared the daylights out of me when she jumped.”

“Girl? Jumped?” Rick hadn’t heard this part.

“Why sure. She jumped. Like it was a slide. Sparks everywhere.”

“Wasn’t the birds? Have to scrape them off sometimes. Birds love it here. It’s a sanctuary.”

“Sabotage?” Willy asked.

“Since the KGB bombed Munich, I doubt they’ll trouble us. The Voice is still on the air.” Rick nodded at Willy and smiled.

“What is it?” Emma was intent.

“Gypsy business.” Rick attributed all the radio’s problems to Gypsies; he couldn’t blame the blacks, like at home.

“Yeah?” She tugged her hat over her ears, not wanting the tops to burn.

Rick was no help, greasy and sweaty standing in the sun. He had an irritating little beard. He had no real interest: the posting was just a career move. He was a heel.

Willy cut short any admission. He had enthused about ghosts when he was a kid, devouring ghost stories, making a pilgrimage to the Library of Congress to comb the archives for photographs of mediums and séances. The pictures were doctored and folksy but it must have been convincing at the time. Yes, he had been gung-ho, even published a fanzine on the paranormal, with the editorial help of his favorite writer and correspondent, H.P. Lovecraft. It was fun being scared. But what scared an adult was completely different: nuclear Armageddon was high on his list.

“Only jazz can save us,” he mumbled to himself.

“What was here before?” Emma asked. “A graveyard?”

“Marsh. The water table’s too high for graves, sweetheart. Dead float back up. That’s why we don’t have no basements.”

“Ever invite a priest here?”

“No, ma’am. US government property.” Rick stamped at a tuft of grass.

Emma nodded. Infernal. They were getting nowhere with the bureaucrat. But, she reasoned, who expected to take the two eccentrics seriously: the pale DJ and his sunburned wife?

They settled in the canteen, a neat array of aluminum tables and chairs on the lower floor of the main building.

“Any theories?” she asked Willy.

Rick had returned to his office.

“Let the little girl go, Emma. We were tight.”

“We could camp here tonight. We won’t drink.”

“How long will that last?”

“It’ll be great. Remember when we drove to Ed Gein’s house.”

“That was great?”

“In retrospect, macabre, but yes.”

“Uh-huh.” The magnitude of what he was going to say needed a pause. “We could make our own little girl instead.”

“Hogwash!” she blurted. “You don’t even like children, you stinker!” She did hope, however. This wasn’t the first time he’d brought up a child without her prompting.

“How about a séance at our place?” He knew that would frighten her, calling for the undead.

Willy Reed was a good medium. He’d entertained his teenage friends plenty when he dropped his voice to the deep bass that it was now. He could lift a table with his foot, talk in wicked tongues, make signs and move objects with telekinesis, barf up cotton wool like ectoplasm—his rebellion against the Reed household permeated with a strict sense of religion. He had wanted to see death in reverse.

“Please ask Rick. It’s not like we’re double agents.”

“The problem is, Emma, you never know.”

Willy didn’t argue with Emma’s idea of adventure. If this was the penalty for her happiness, Willy was fine with it.

They bivouacked, with Rick’s permission, under the zinc roof of the parking bay, but not before returning home for their ghost-hunting gear: the camera, reloaded with film, and some warm clothes.

They shared a campstool and a mechanic’s cot marked with grease and miscellaneous stains. Between rounds of cards, they watched the towers.

As they tired, eleven o’clock having passed, they divided up the watch, Willis chain-smoking, Emma napping. And nothing came. Nothing. No lightening. No shooting stars. No fireflies. No ghost girl.

It was no more uncanny nor untoward than any other night.

“The ghost’s hiding,” Emma said.

“But there’s people working here 24 hours a day. Surely, the ghost isn’t afraid of us?” he replied, stubbing out a cigarette. “I’m the one courting it anyway.”

“You and all of the Soviet Union, baby,” she said, her hair chopped into chunks by the rough accommodation.

Emma glided through the day and the rocky beach reached by the flimsy door was an afterthought to her appetite, awakened by the ghost child.

As a distraction, Willy splashed out for a proper restaurant in Pals, the Coach.

It was empty and they were treated to the complete attention of the chef and proprietor. Lavished with food, so exquisite in its simplicity and freshness, they were left breathless. Emma liked the chlorophyll foam that accompanied her goat ribs.

But Willy Reed was distracted anyway, thinking of his Polish X-ray recordings, the calendar, the interviews. He needed to prepare.

Through a mix of Emma’s Spanish and Willy’s sketches, they managed to ask the chef about the specter.

“Oh, yes,” the chef said. “Danger, no.”

They looked at one another in bewilderment.

“Towers. Here. Tempest. No normal. No, no. Gitana. Americano. Negro. Towers. Amore. But go. She. Baby. Papa. Baby. Tradition. No dead. Fishermen. Fish. Baby. Gitana. Tempest. Pequeño. Pals. No superstition, no. True. Papa. Danger, no.”

They deciphered it.

“Damn!” Emma jumped from the table. “That lousy attorney! He’s the one! That’s why no one’s at the house at night. It’s haunted! He’s no more attorney than I’m Dusty Springfield.”

“Oh, you’ve gotten ahead of yourself, Emma! Think, woman, think!”

They ruminated over a honey aguardente. Willy savored the hard alcohol.

She screwed her nose at it. Foul.

“What if we made a baby for her?” Emma asked.

Willy raised an eyebrow. “Right here? Now?”

“No, silly. Bake one.”

It was ridiculous. Emma gathered everyone in the Coach’s kitchen to make a baby out of dough.

Yeast required time they didn’t have so the dough was a shortcut, mostly salt: the ghost girl wouldn’t be too choosy about the taste of her baby.

Willy rolled out the arms and legs, the chef worked on the head and diaper, and Emma decorated the trunk. She did nice hands and feet.

Then they had to wait as the baby baked in the wood oven.

The restaurateur kept everyone lubricated with just the right dosage of coffees, liqueurs, and sweetmeats. Emma refrained and drank only tea to fortify her mind.

Crammed in the restaurant’s van, the party hurried to the beach.

No sooner had they removed the baby from the back, clad in a napkin and sucking a cucumber pacifier, when the electric squall started out at sea. They walked hastily, the drop to the water short and sharp.

It danced, apprehensive, then came strong and fast.

They frog-marched the baby to a spot under the towers, placed it at the base of a mast.

Was it convincing?

Emma held the camera. Willy gripped Emma.

The restaurateur hugged Willy.

The blob of energy stormed forward. Screaming and wailing, cascading bolts of plasma. Its face was rotten and flayed. Its hands were mitts of fire. Its hair fell in showers of sparks. Enraged, in full display, it turned and fled like an angry ape. It soon reached the top of the tallest tower, a trial of sparks falling down the face of the radio curtain, and leapt, landing in a crouch of yellow fire.

They backed off.

It sang garbled furious lullabies and loped to the perimeter fence. Cooing, it crawled over and retrieved the baby loaf.

Emma surreptitiously snapped the camera, risking an attack.

A long ragged slit festooned the ghost’s throat, leaking milky white blood. It nurtured the bread baby with a ragged breast. The baby struggled and the ghost angered. It tugged off a baby finger and ate it, then tasted an ear, a toe. It loved the salty baby who emitted a startled cry.

The antennas began to pulse, outlined with a drastic burning halo.

Ghost and baby vanished and quickly reappeared in the highest horned girders of the towers.

The entire system surged in intensity and began to blow.

A tune started as static, under it a rippling bass, distorted and twisted like sheets of torn metal, and rose to a cyclonic shriek.

Ghost and baby waltzed in the heights.

Power collected in the towers. The sky was bilious and purple, tense. The towers bunched together and bent into a vast organ of horns and open valves. The reeds blew and blew, giant black notes bouncing off the tumultuous sea.

Rain strafed their faces. They fell to their knees. Their bodies began to cook.

Then it leapt, clasping the infant loaf.

The sky crackled at that instant and ghost and baby were banished.

Willy dared cough a few minutes later in the stupendous silence.

They congratulated one another heartily as they brushed off the sand. Emma was the star. The baby was her idea. Willy smiled at her, like him, phantom, Christine, unredeemed.

He looked at the towers, the great parts of his sax in disarray, the curtains torn and loose. He knew they couldn’t last. But he couldn’t either. Willy Reed was an anomaly, his time over, the end in sight. Already satellite dishes handled the feed that was once relayed with tapes sent by courier. Soon America would win and the jammers would fall silent and he would be without a purpose or a job.

In the future, just unwanted landscape, a tourist attraction, they would be removed and missed. It was like taking away jazz: far too painful to think about.