Cowboy Atlantic

A mystery at the library in Baia Mare

On a mild Good Friday, unconcerned by intricacies of history, a pretty companion and I strolled along the leafy streets of Nagybánya (Baia Mare).1 An abused brown river gushed from the deforested hills that cradled the strategic town along Romania’s northwest boundary. We had honored the fast so far, purposefully hungry. Anyway, I was distracted by low-hanging fruit of another sort, a stunt and a hunch, matched with a dose of fuck-it-why-not.

“Such a long shot,” Lia said.

She shrugged, then pushed through the black doors of the gray communist slab that was the county library. Next door, another monolith, the sooty white Carpathia Hotel, was decorated with cement horns and reputedly the home of a well-stocked sauna.

The muddy grumbling of the Săsar River muted as we entered.

The receptionist, hair lofty in a headband, body in silver dungarees, insisted on a photo for a library card before continuing. I wasn’t planning on visiting that long, but my goofy smile made a cute memento. She then marched us to the librarian’s office.

Ioana wore a white dress splashed with inky spots.

She listened to my request as Lia translated: “He’s a researcher from America. Do you have any records about the cowboy circus of Buffalo Bill on approximately July 17, 1906?”

The request was too abrupt, too precise for this sturdy woman in a flowing dress. I shouldn’t turn up on a Friday that even Orthodox Romanians regard as half-off, at least in Transylvania.

“You’re too late and on the wrong side of history,” Ioana relayed. “We haven’t any newspapers from that period. Or any memorabilia. We became the county seat of Maramureș after 1919, and everything was tossed into the streets and set alight. Go to Sighet and look there. That was the county seat in 1906.”

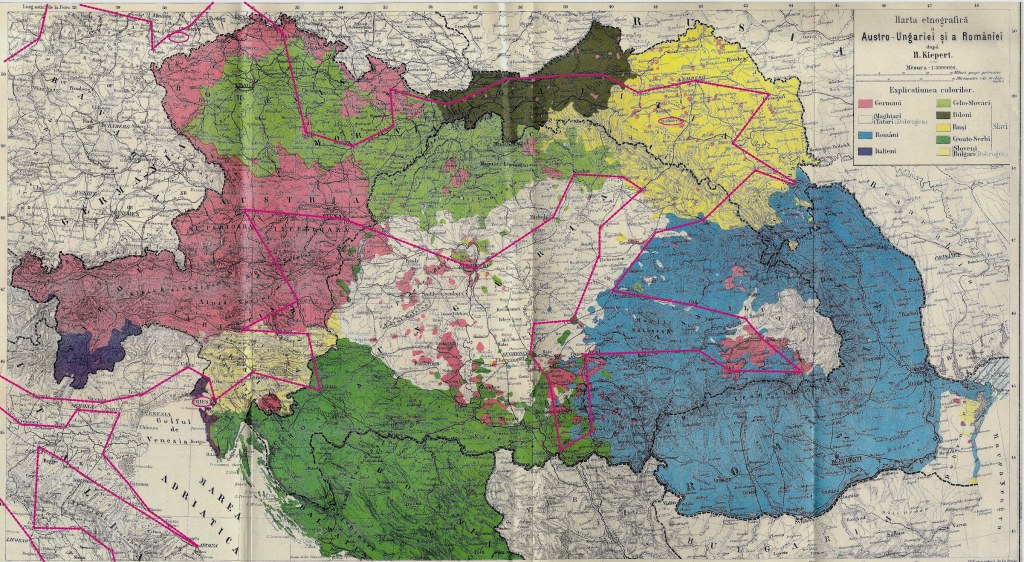

I hadn’t expected any lead, and this confirmed my suspicions: Maramureș County was one-third of its original size, divvied up among its neighbors; any materials from a meticulous Habsburg record had been removed to Budapest well before the signing of the despised Treaty of Versailles at Chateau Trianon in 1920.

“Call Echim in Sighet,” she said emphatically. “He knows everything. He’s got the newspapers.”

All I sought was confirmation that Bill’s magical show had stood here, if only for one day of the twentieth century, enough time to impress the town that America was both rich and powerful, both refuge and paradise.

While she jotted down Echim’s information, Ioana sparked my interest with a piece of intrigue, an account2 of Maramureș shepherds who migrated to Montana in 1907 and returned with their profits by 1917.

Had the shepherds seen the dayglo handbills from Buffalo Bill’s Szatmár or Sighet shows in 1906 and come to America thereafter? Was it likely? Montana and Maramureș share green sweeping hills that engage with high mountains and a labyrinth of woods and meadows oozing with game. They share merry mountain songs as well as dirges and spaces where the land is harvested for meat, honey, fur, gold, oil and timber.

Later, a modem connection that might as well been puffs of smoke disgorged a request for an appointment for the first available day after Easter.

Lia’s tiny flat was awash with her mother’s culinary preparations: lamb’s head and sorrel soup, offal-stuffed lamb, braised lamb liver, roasted lamb legs, polished radishes, sparky onions, pyramids of stained eggs, tinctures of schnapps and village wine, snack cabins hewn from homemade cheese straws, and plates of homemade cakes with names like harlequin, wasps’ nests and Linzer.

Put off by the gluttony, Lia disappeared to visit her aunt. I pretended to struggle with the food. I mocked a protest and winked, “Not one morsel more,” while Lia’s mother buzzed around.

Bursting, I excused myself from the cramped flat and wandered to the center. I photographed the earthy pastels of the old gates around the plaza. Not far, behind city hall, I found a bowling alley, next to a run-down cinema. Entertainment and culture seemed to have lost its luster for the clump of people drinking wine from a plastic carafe, gleefully in despair on the broken steps outside.

There I imagined who might have been that ephemeral Bill who traveled here a century ago. Like any man, at some point in every day he felt like a loser, even when life was grand.

Adrift

A somber Bill in Habsburg

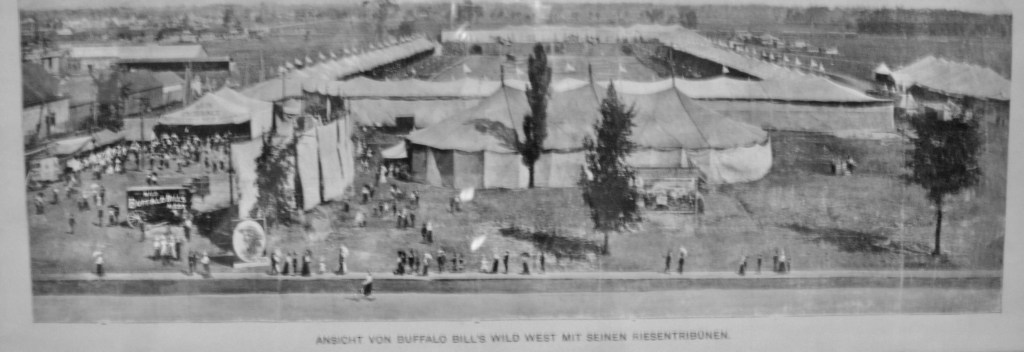

The tents went up in the morning. Three trains were parked alongside the lot. Bill and the dignitaries, the actors and performers, the animals and the hands.

He was hungover during the matinee, which was for kids anyway.

Bill parked in a café for the afternoon lull, drank under a parasol, flirted then bothered a cute customer, dispatched a boy for fry bread – popular with the Show Indians too – and improved his mood for the evening show.

All he had to do was mount up, ride out under the lights and listen to the roar.

The European towns surprised him, brimming with artisans who were missed sorely in frontier towns. Tailors, seamstresses, tinkers, smiths. Merchants with their stores dispensing fine cloth and oriental luxury at the ragged terminus of the Silk Road. Still the rope wasn’t the same and neither were the hats. They didn’t treat their cattle the same either. Remote villages, powered by water and wind, felt as old as civilization itself. And their fruit brandy was crackerjack. Yet he noticed they were soft, bowed and oppressed and he offered something wilder – progress, destiny, the test of civilizations, then men – freedom

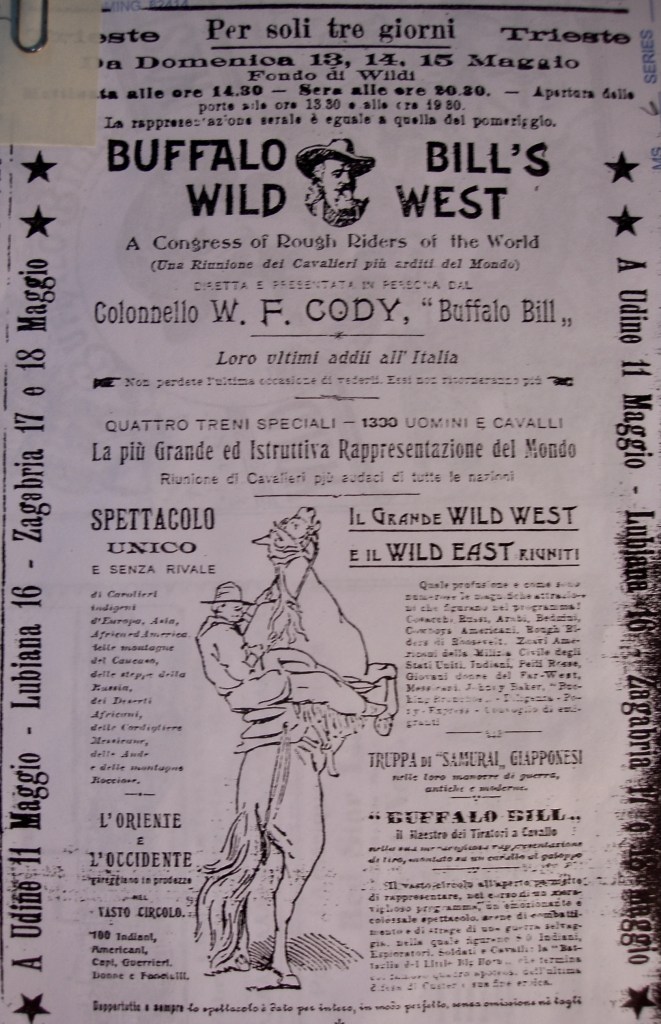

He needed these people back home – he’d raised a town of cob, sod and lumber and watched it fold – and his agents littered the route with handbills for Cunard passage from Trieste or Odessa to New York. Afterall, he was handpicked as America’s foremost cultural diplomat to dispel the reputation that the United States was no more than bandits and brutes.

No, he was as modern as they came: men weren’t savages and women weren’t the lesser sex, at least that’s what he concluded when he was bent in half after days of snouts – any excuse to revive his brio.

The kids looked at him the same stunned way, like a giant among guides, part cowboy, part native. True, at 6’4”, his face powdered red and a feather akimbo at times, aloft on horseback, he appeared to be a grand specimen, albeit bedraggled in places. He had been kicked from place to place like a flat ball at this stage, one of his lungs black, topped with buffalo fur and prairie dust, the other ivory, poured from candle wax and perfume. Bill was alive because had unfinished business, wages and women moving through his morbid hands like mice. He’d always relied on two, two horses, two kids, two women, when the number should have been three, a wager like a kerchief that has more uses than a hat.

Sigmund had advised him in Vienna what he needed to survive, his wit, spirit and soul, where he would dive from home to infinity, yes in the east, like at home fearing to cross on the first of many mountain divides. Why forgive when he could accept? He hugged the alpine heights, stayed up top and away from the bottom, where he felt distracted, impatient and low.

The men parked their animals and transport when the day was done, market and milking over, work and money collected, mines belching out ore and men, and they gathered in the saloons, sawdust floors and blocks of ice on the bars. Some were building a reservoir, they said, and a smelter and mills. They erupted from the gravel and mud roads and ten city gates into the main square, hailed one another at the roundabouts, cursed when they had to walk further than necessary among monuments to poets and figures honoring the monopoly of humankind.

He laughed himself into his buckskins. The audience never knew performers were neither laborers nor slaves, but part owners, meaning they only got paid after he did.

The wind upped with the setting sun and whispers blew the ringlets of his wig, falling that much more spectacularly at home in the head-high grass. The folk, instead of coming from everywhere, they came from one place, rooted, advantaged, exchanging grafts and seeds, kith and kin, as much as he hadn’t been home, some amorphous resting place where he was troubled by his estranged wife’s nagging. Scout’s Rest was Luiza’s, and she was running it into the ground however she liked.

It’s hers, he concluded again, shaking his head.

She’d underestimated him when he gave it up. He was savvy and she thought him an imposter, unconvinced by his every elaboration. She hadn’t liked that patch of glorious land when she saw it and now it was hers. He sickened at the irony. He spent Easter weeks in Rome and then the Pentecost in Budapest. By October he could leave Europe and by Christmas he was home, the pine bar in New York City, his pasture Central Park, glassed up on stage, on show in Staten Island or Erasmus, he couldn’t figure without looking at the route book.

Never Accidental, Never Serendipity

A clue in Cody

This search was purposeful and orchestrated once I saw what I needed. I was back in Goshen grasping for anything to occupy my mind. I couldn’t gut a ranch house of family relics all summer long, dragging heirlooms, crockery and junk out into the prairie for the auctioneer, without a break.

To alleviate the job, I sought out John, a salty character writing Western pulp fiction sold at truck stops across America to this day; he hid out teaching English at Goshen Community College when not hunting on horseback. Although not a reenactor, John enjoyed observing some of the kinks of the Western lifestyle, and he asked me over a Dos Equis if I wanted to drop in on a writers’ conference on all matters West in Cody.

“Sounds cool and offbeat, John,” I said. “And it’s only seven hours away.”

Some days later I caught a ride together with John and his family; they seemed unimpressed by the adamantine canyons peeling off the Bighorns on the way to the southern gateway to Yellowstone.

“Some of the conference members have trouble separating what’s fantasy from what’s reality,” he said. “It’s a little unnerving when you’re sitting next to a guy who thinks he’s Wild Bill Hickok.”

He chuckled at the thought, shaking his head, nudging his hat.

Soon I was roaming through a cowboy agenda punctuated by handshakes, whisky, cigars, steaks, poker and the crackle of mock gunfights outside the motel.

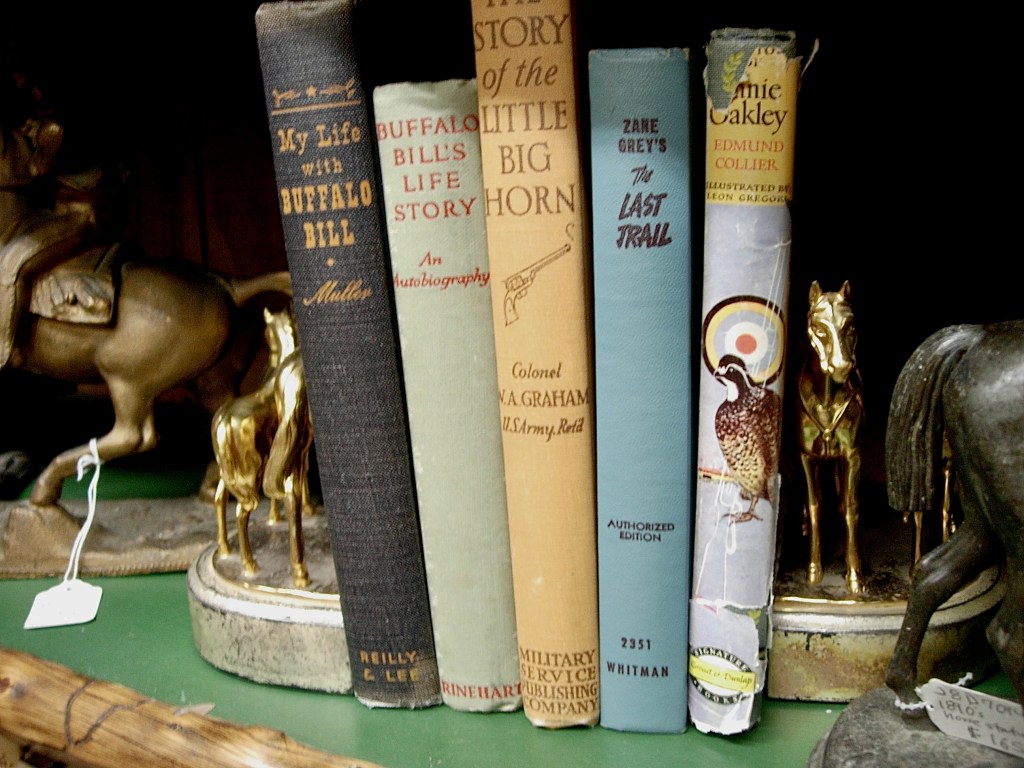

The conference was a hoot, but I needed to pause from all the bold talk of heroes and villains who dwarfed the everyday characters and cultures fatted in the underbelly of the discourse on America’s West. I sobered up enough to nose around the Cody Museum, sarcophagus to the legend and keeper of his memory and memorabilia. The collection was not without controversy regarding its blood trophies taken from the First Nations. The museum was trying to catch up with the echo chamber of America’s cultural debates, sensitize itself to the trauma of exhibiting guns that killed so many tribes and nations, but that attempt was muted by a gung-ho board and the sheer weight of tribute to William Frederick Cody who’d led the extermination of buffalo and therefore won his name.

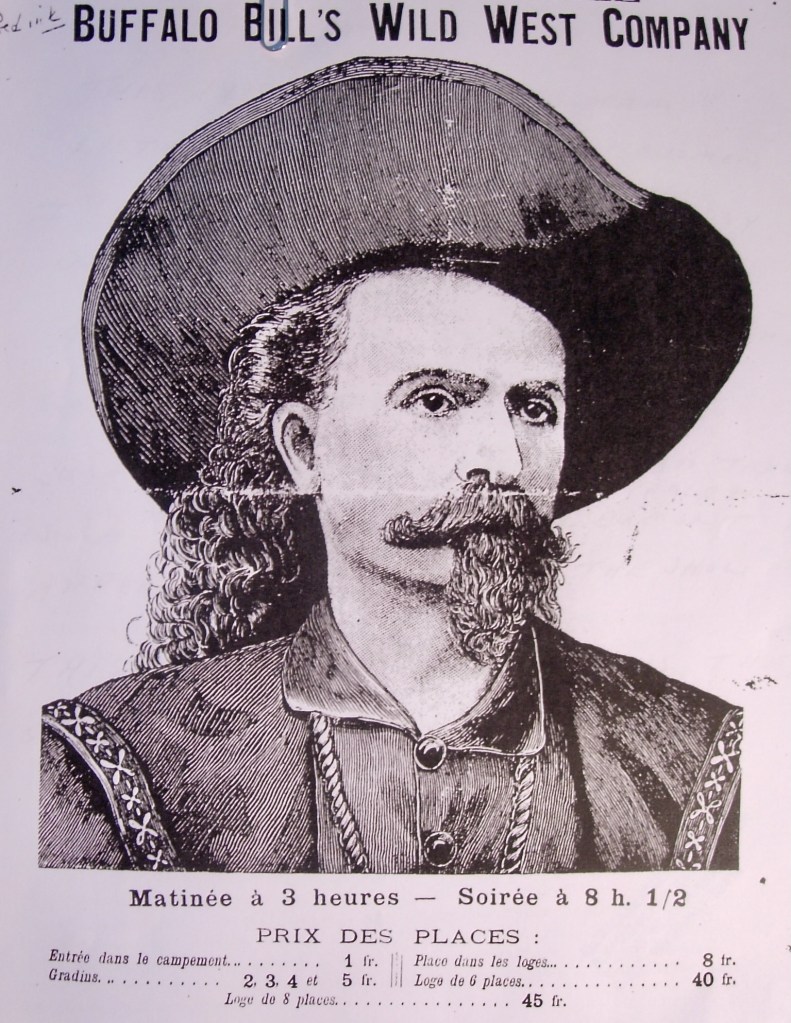

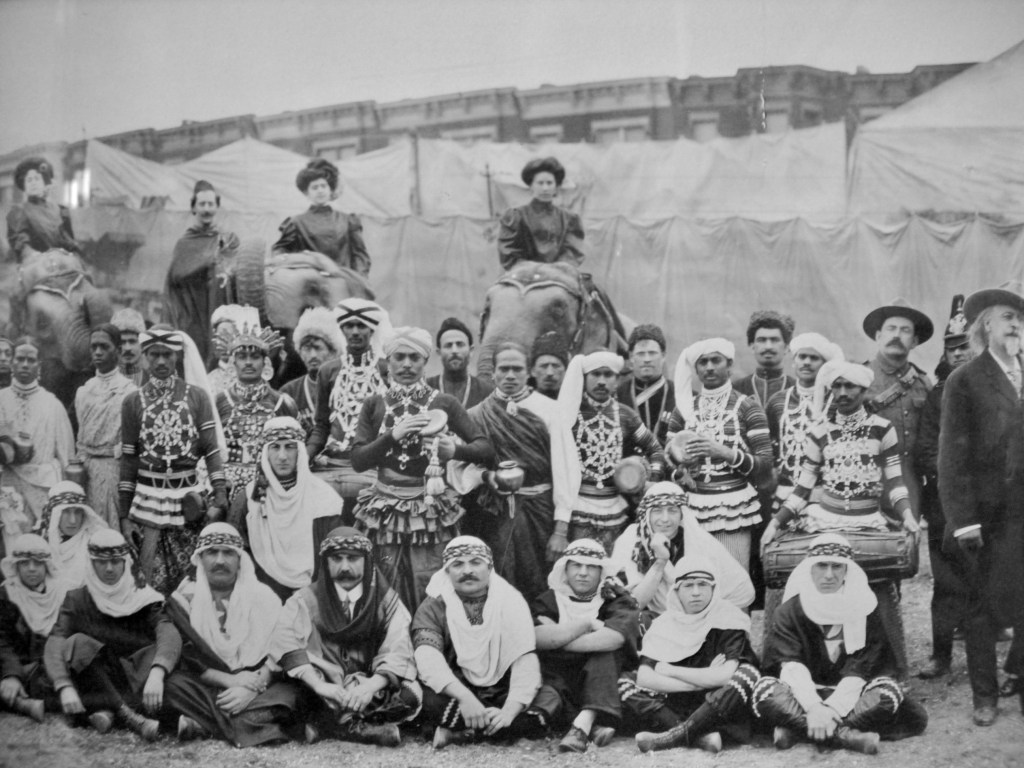

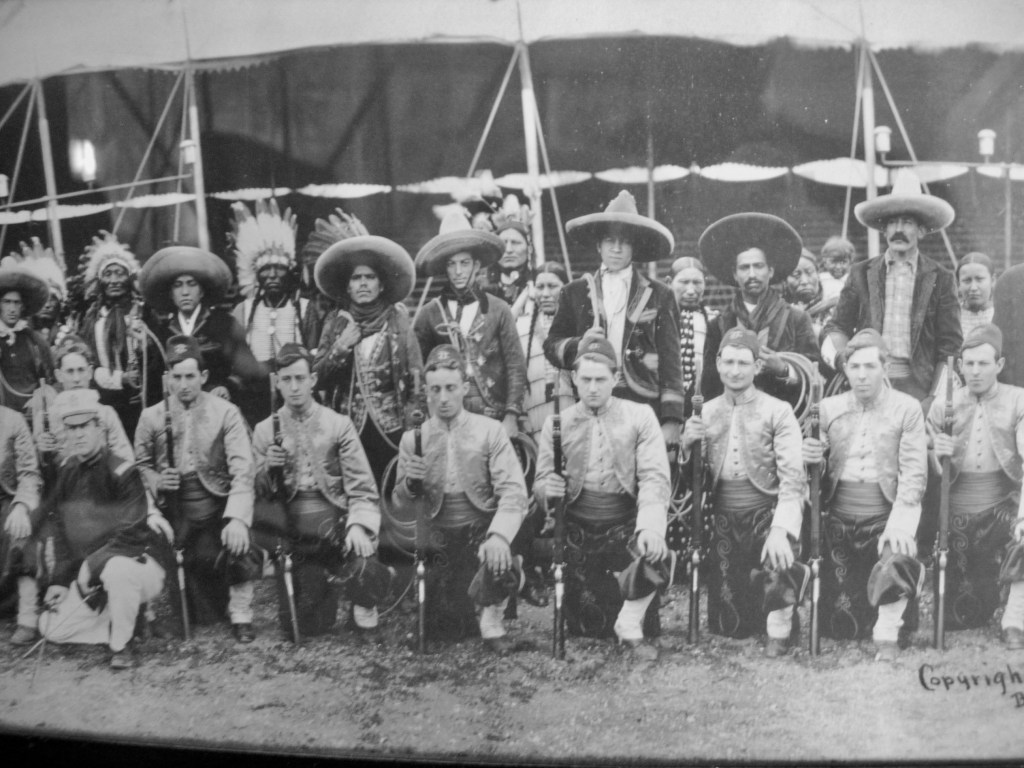

I perused cases of uniforms, guns and equipment, studied dioramas and mannequins, read letter excerpts and ephemera, sifted through the errata of a man and his show that spanned the birth of American exceptionalism. They’d tried to present the multicultural aspect to his roaring international Rough Rider cast in showbusiness, his rehabilitation of Native Americans who had been consigned to the dumpster of history, and his role as America’s first cultural ambassador touring America and Europe. None of those superlatives could cover up his role in the body count to win the West.

One item leapt out at me that afternoon of told and untold.

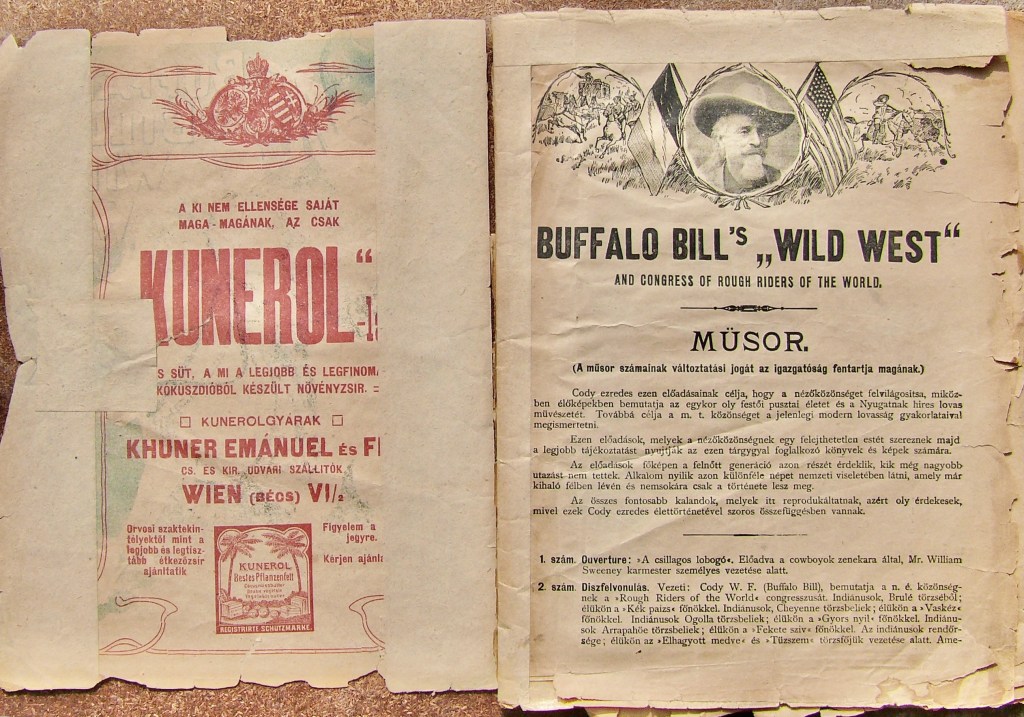

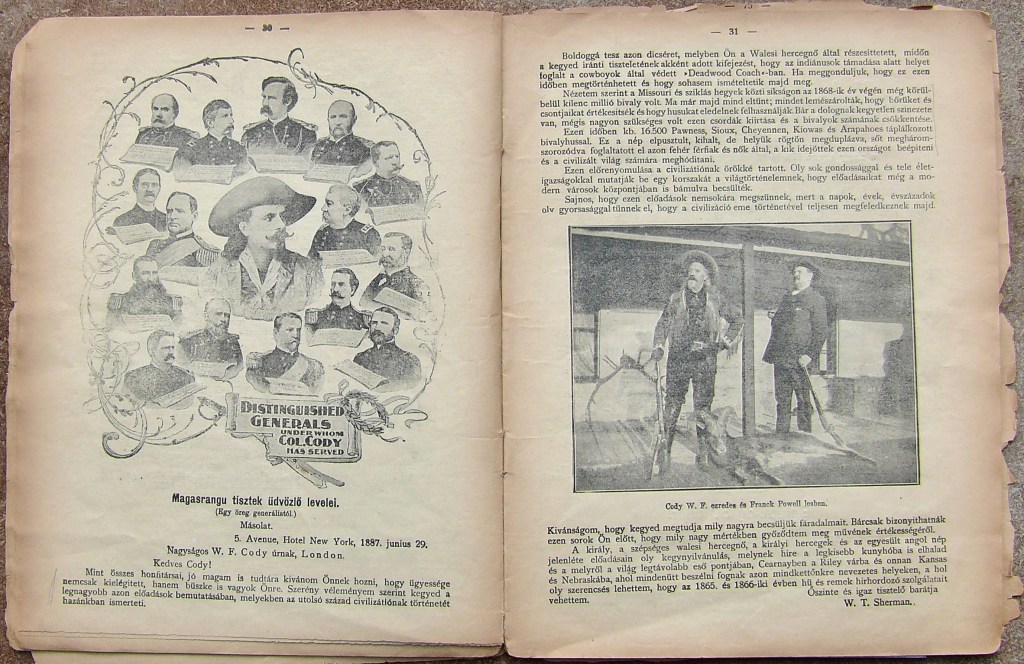

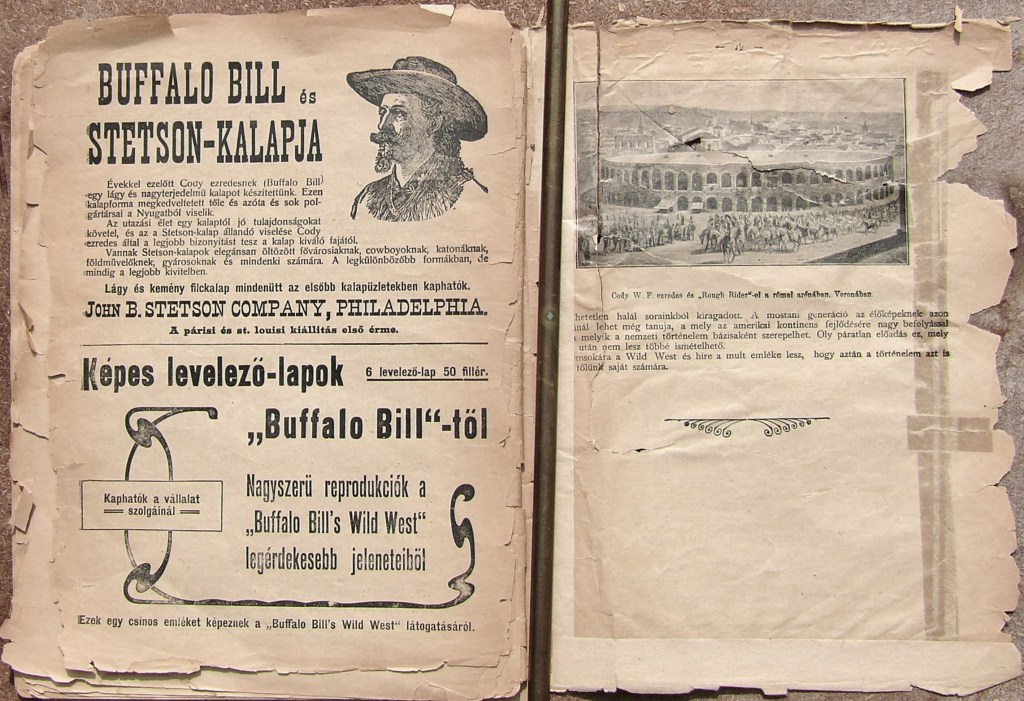

There, lodged in a display framing his European career, I spotted the unmistakable umlauts and diacritic marks of the Hungarian language.

How could that be?

Had Bill gone to Budapest?

Not in my wildest dreams.

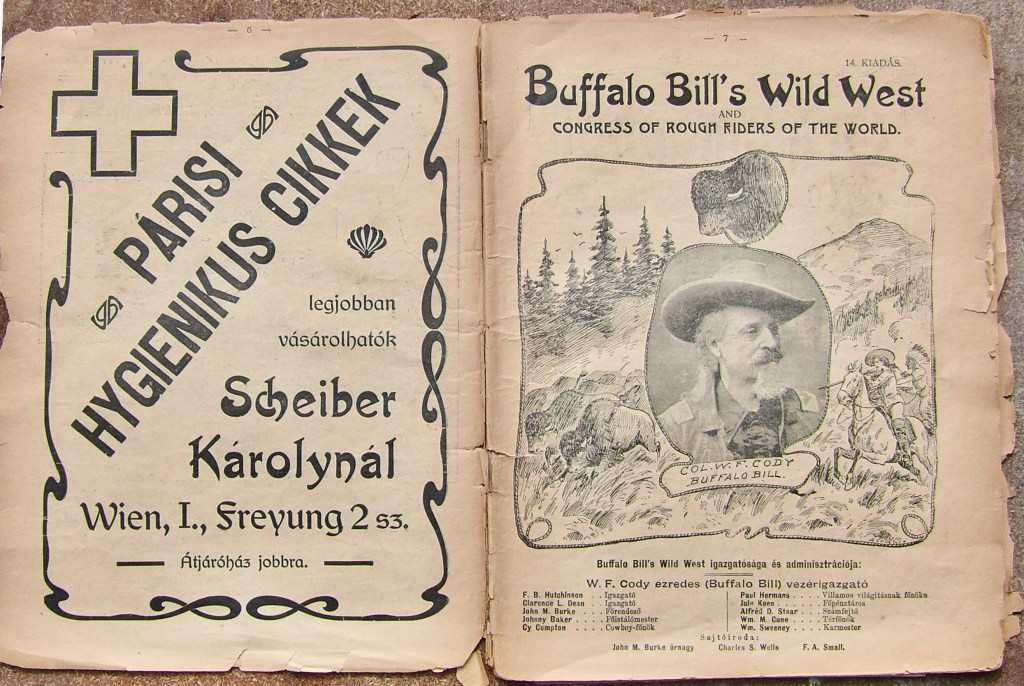

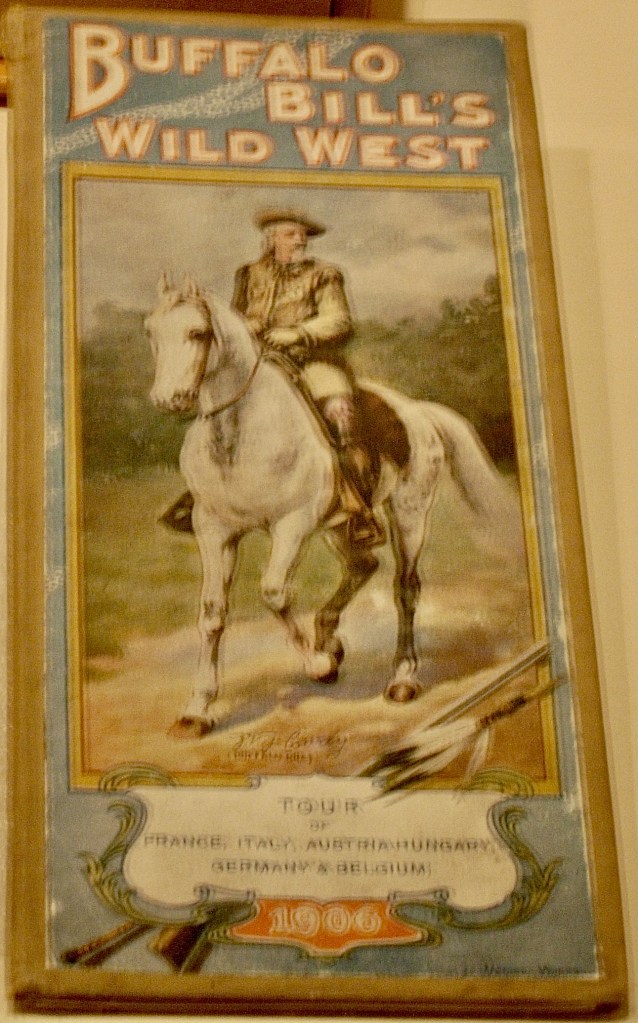

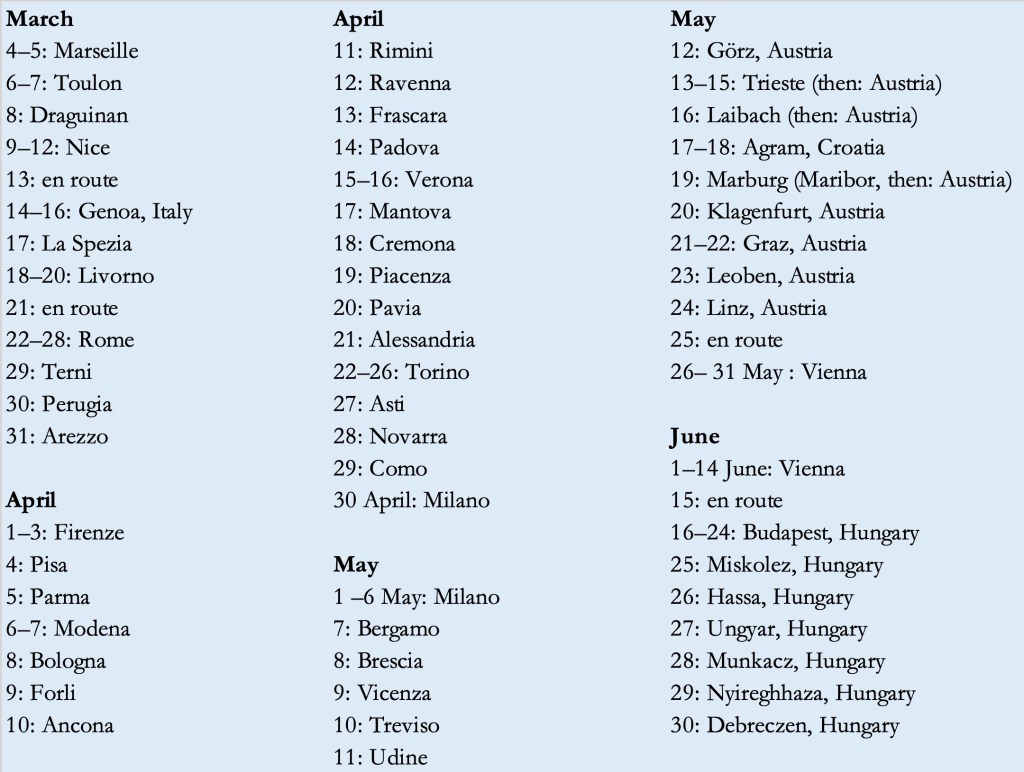

Yet it was undeniable: a souvenir route book from the Habsburg tour of 1906, Bill’s summer farewell to the breadth of Europe. Yes, it had been translated into Hungarian and clearly displayed the date: July 4, 1906, American Independence Day, which could only mean that Bill had toured my adopted home of Hungary and its neighbors if history was to be believed.

This unexpected clue inflated in significance by the second and almost seemed to account for why I’d drifted here, wherever that here was, a home somewhere between continents and oceans, paper and mind, past earth and present sky. Suddenly, there was a lot to investigate and many more questions to ask back in Europe. Only later, when I had proof this ephemera wasn’t a token glimpse or mirage, would I return to see what of Bill wasn’t on display.

To me it seemed Bill was as alive as Elvis, with all his flaws, in all his glory, synecdoche and totem for America.

Red Hand

Bill appears on family land

Bill rolls the truck to a halt next to the battered homestead filled with dry manure and a lonely chewed up mattress. Brittle elms. Water tank’s empty. Weeds. He edges through the barbwire and stomps across the field, his scabby boots kicking at the tufts of prairie grass and cactus. Not his place but near enough. He’s risked walking in and gambles a feisty old rancher won’t turn up for his steers or shoot crooked imagining he’s rustling cattle or staking uranium claims.

Bill walks toward the hills dotted with rock and cedars, dark green like yeoman. A hump shades the entrance to the canyon. There’s a waterhole and the wind has blown the blond sand away to reveal some darker black scarred earth the color of fire. Scattered with chips of flint and chert.

Water has seeped here into the prairie for millennia. He’d want a drink too if he were that old. Some days it feels like it.

The house is hidden by a fold in the earth. The valley opens in front of him, his feet wedged in the ruts of the jeep track.

Bill’s killing time, waiting to combine corn on his irrigated land. Still not dry thanks to a funny autumn, and no hard frost, he thinks. Shouldn’t be too long once Bill gets the signal that the shucks are dry enough. The boys’ll harvest 24 hours a day under klieg lights. Shame that the corn will be brewed into ethanol under the primitive sky.

The geese and cranes have been gliding over like an orchestra of brass and woodwinds making harmony. Bill grabs the scuffed field glasses and studies the creek. Wild turkeys are the game he’s most interested in. They hover along far out in the prairie until they come for water, and he might bag one. A fantastic shot, maybe he’ll be sober enough to shoot a black hen fat like a bauble.

Bill heads to the cave at Wildcat Canyon. The wind nearly steals his heart, it’s blowing so evil and hard. Inside the cave under the lip of the canyon his name is carved alongside the date. He returns 52 years, one day, and one hour later to the exact same spot where he had carved his name along with three other boys, Bob, Ray and Kyle. On the wall opposite rests a bright red hand, an ochre petroglyph, the marker for an ancient burial site, a signature, distorted and made huge, rough and prehistoric, a language. A fine place to hunker down and hunt, the cave big enough to hold a fire, a tongue of broken rock reaching from the bright entrance down to its dark floor.

He shakes his head as if to escape any blame from the land. “Sorry, I didn’t write it,” he says.

He guesses that must be why he’s in Wyoming at the edges of old territory of Mexico. Bill corrects himself, knowing he shouldn’t sum up that controversy to people round here, that there’s a contiguous history flowing along the Sierras and Rockies, that it’s the same conquest no matter if you’re Montezuma, Pancho Villa, Geronimo or Red Cloud.

Powered by his thoughts and desires, he skips visiting the farm and drives into Nebraska that night, through the towns of Mitchell and Morrill to the municipal twins of Scottsbluff Gering. The liquor store noticeboard suggests some entertainment is on tap, and he lands at a Mexican conjunto night, the rowdy band made of accordion, trap drums, singer, guitar, washtub bass, the audience drafted from the slaughterhouses in town. He doesn’t want to slurp back too much because he’ll weave along the corridor to Wyoming where too many people eject anyway. He loves dancing with senorita and senora alike, rotund like popsicles, hollering in his fucked Spanish, migrating to mezcal. Twenty years ago it was a dirty word to be a Mexican in Scottsbluff.

Not anymore. They got pride.

Ahh, it’s good being here, Bill thinks. Uncrowded. Doesn’t rain at all. But could be cold or windy, in a way that would yank your teeth from your gums.

People think it’s a flyover state but they’re wrong. It’s America’s Siberia, full of resources, prisons and bears. And if they’re short on rations, they can drive to Walmart. If they need company, they can hang at the town bowling alley with a fair share of end-of-roaders, deadenders, lunatics and oddballs who make life interesting in a mad, paranoid, armed way, so long as he avoids direct eye contact.

Bill feels better with the idea of the cave, huddling under the talisman of the red hand caressing the rock face. His breath collecting around his head, it felt better than the museum of objects and memorabilia which overstated so much of his legend. He couldn’t stand the place as much fun as it was to remember as time shifted through his fingers.

Marmot Island

More clues in Sighetu Marmației

The Easter gorging had been performed, the lambs and cakes consumed and now the mountains beckoned.

The mood blackened when Lia announced that her brother had a crackling smoky tumor so large that one lung had to go.

I was despondent at the news. Like so many ignored in the abject poverty of the transition, he was collateral damage of a successfully failing system. He survived fixing TVs and drinking meths. Cash handouts from family and friends went to rotten firewood and spongy bread. Pleas to re-train were met with indignation. He even may have relished being a martyr, the tumor his triumph, his auxiliaries not Dismas or Gesmas but Brenner and Eastwood, his attitude as fierce as any gunfighter making order before imminent death.

I itched to exit the family drama and get out of town, and Bill was a convenient excuse.

Echim was waiting.

The company vehicle of Transport Ruta 66 pulled alongside our stop. The minibus bubbled with teenage girls, who were amused by us, far too eclectic and western in our dress. We assumed our seats, the bus bucking past the gold mines that made Nagybánya tick.

Prefabricated housing had been dropped near the pits to accommodate the miners, and trees now greened the area, undeterred by a combination of cyanide-laced slurry and smelter fumes. Bursts of color were a testament flagging the past: in the upheaval postwar states had to house their people who had been displaced by forced population exchanges as the Allies portioned the map; states had to provide something, no matter how basic. Here, out of range of the victors, communism was marketed as the way out. If they once had sold revolution, now they sold utopia.3 Panels were glued together like ideology, complete with schools, co-ops and Mineral Bars, for drinking was a patriot’s opportunity to loosen up.

The switchbacks curled through beech and larch forests dashed with moss, sparkling with spring. The bus yawned past the ski area of blank, bald runs, coming to a stop at the cabins on the summit. The villages dwelled deeper down. Chartreuse oxen tugged lumber wagons as we jogged on. A pause to let off young women in jeans and cropped jackets, jumping down confidently onto the land. The pretty hills hosted gloomy wooden churches of Budfalva (Budești) and Felsőkálinfalva (Călinești), their sides stenciled with horrific accounts of Biblical ruin.

The road busied at the approach to Sighetu Marmatiei, the birthplace of Elie Wiesel and Amos Manor, a founder of Shin Bet, along with a handful of instrumental organizers of Zionism and the Teitelbaums, the glamour of Goldwyn Mayer and the tax-free kingdom of the Khazars. Not far from a geographic center of Europe – notorious for its decommissioned prison, the end for many counterrevolutionary, a bloody tangent of history commemorated as the Memorial of Victims of Communism and of Resistance – Sighet is the laser focus of this historical footnote, host to Buffalo Bill’s tour on July 26, 1906 looping its way northeast, when three trains pulled into the station, eight lines of siding, the site on now which chugged with scruffy local transport.

Lia and I boiled in the sun and shook in the shade in Sighet. The place seemed to hardly have a map until the wormhole of the agronomy museum among the Habsburg buildings and traffic routed one way on each side. No contemporary signage spoke about the largely Jewish population years ago.

The library was emboldened by a turret, and we entered the main hall, flights of stairs roaring over our heads and numerous municipal activities nested within this unheated public building. Along a cold corridor we found legendary Echim, librarian of Sighet, who politely excused himself and left us in his office, piled with folders, a few computers and notices for local jazz, folk and klezmer. Trapezoid reading glasses were tipped over the piles, illuminating, questioning, glowing as if working by themselves, exposing all the potentialities (and fatalities) of this small town, understanding what it was in the past.

When he came back, our inquiry began in earnest.

Lia rolled out the request and the librarian nodded sagely.

“I know about Buffalo Bill because local historians have been very active. We don’t have a full archive of newspapers or photographs from that period. Hungarians took it all after the war. But you know, last week, I bought part of a private collection of newspapers from 1906.”

He grinned and grabbed a large bound portfolio.

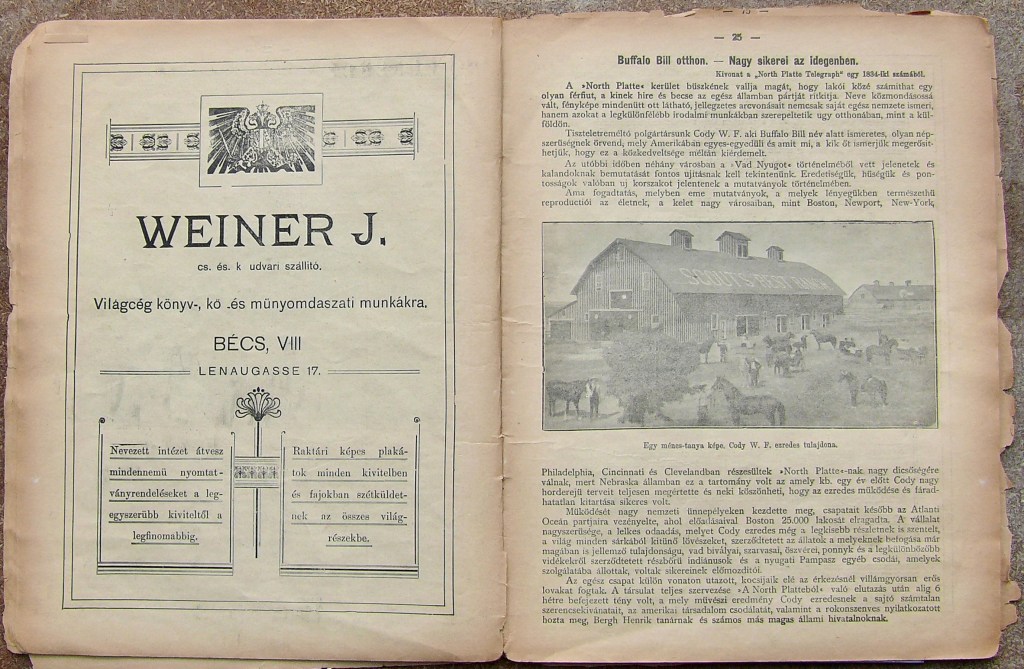

Under the bright blue plastic cover was confirmation that this odyssey was not an illusion. It revealed the departure point to understand how the West came East, how a man born in Kansas, exiled from his spread in Nebraska due to matrimonial conflict, embarked on a 8,000-mile rail tour in 1906, having traveled another 24,000 miles in the previous three years in England, Wales, Scotland and France, excluding the route home each winter by steamer to deliver his Indian performers back to their reservations while the buffalo, elk, broncos and deer were wintered outside Stoke on Trent or Marseilles.

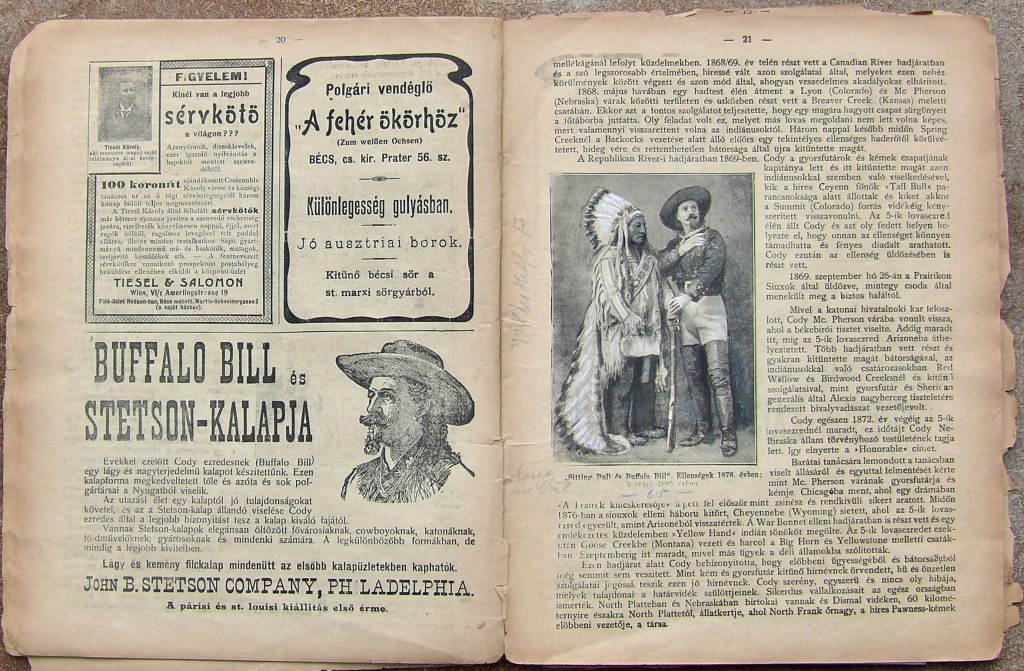

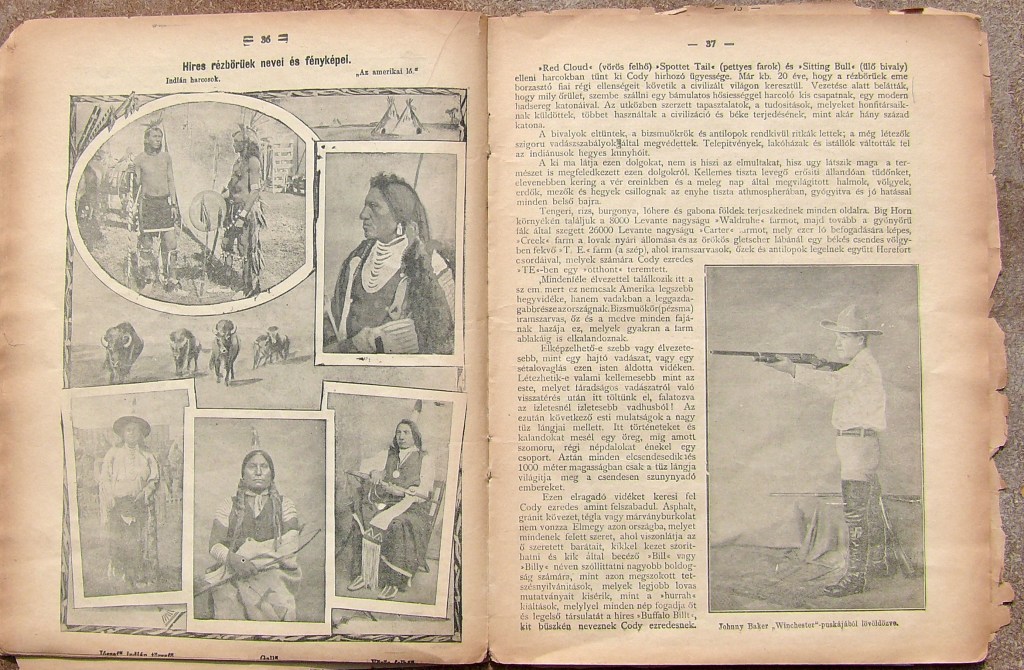

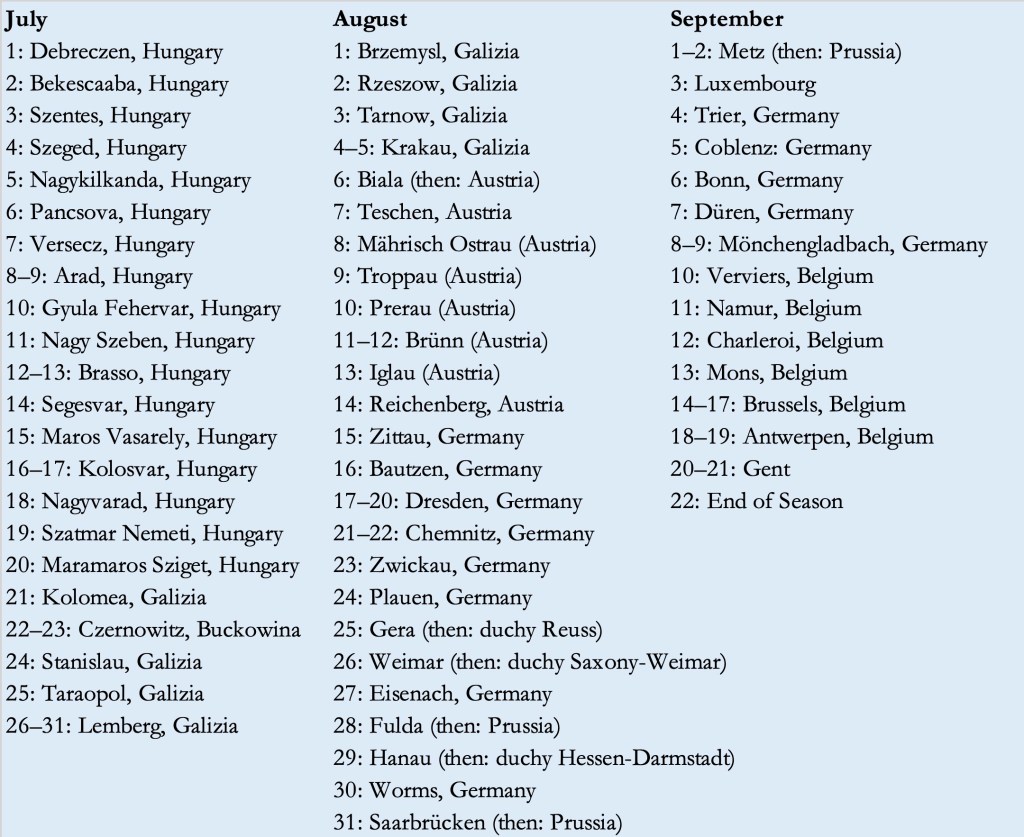

Echim leafed through the 1906 issues of Máramorasi lapok (Maramures news), and it didn’t take him too long to identify the advertisements in the fortnight preceding the show.4 He’d bookmarked them with chits of paper. Placed by James A. Bailey’s press agents traveling weeks ahead of the calendar in the Carpathian Basin, they printed a line drawing of an Indian chief center-stage,5 prominent among advertisements for livery, groceries and remedies; later editions of the paper were decorated with Cunard’s sailing times from Odessa and good prospects in America to encourage the exodus.

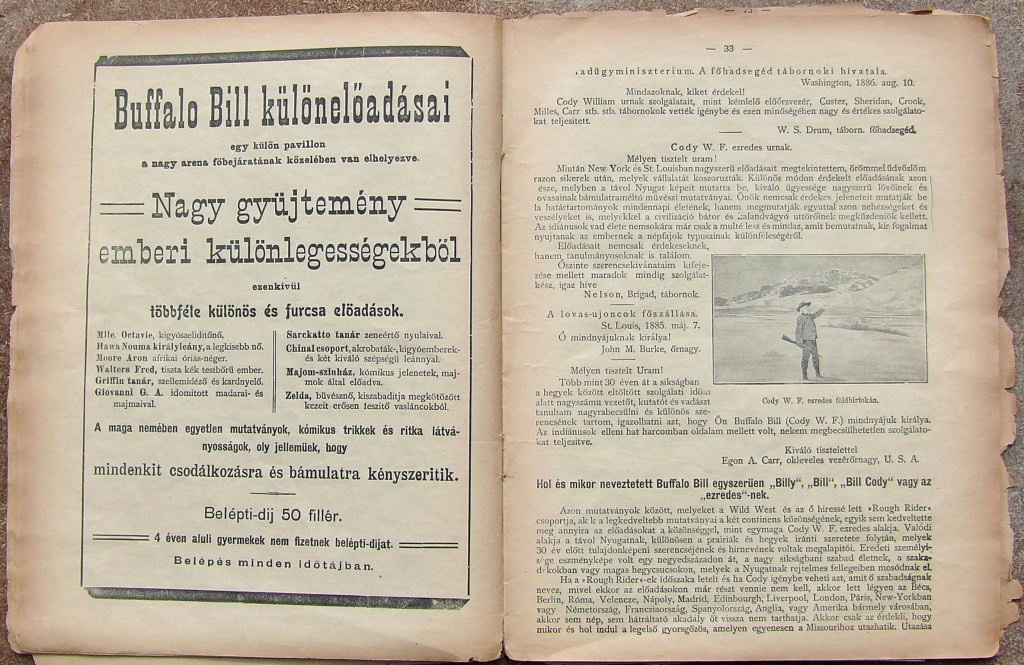

| In Máramarossziget for only one day! Sunday, July 22 in the Market Square Two shows Two o’clock in the afternoon. Eight in the evening There’s no difference between the afternoon and evening shows All seats are protected from the elements Buffalo Bill’s Wild West A Congress of Rough Riders of the World (The world’s most famous rider) Cody William Frederick, nicknamed Buffalo Bill In front of your very own eyes. No other opportunity will present itself to see it again, it’s really the last tour! They’re never coming back. Come to this exhibition. Three trains 800 people – 500 horses |

| An original exhibit, unique and incredible The only one in the world The one and only and universal union that until now was never seen before. American Zouaves and other civil soldiers of the United States. Arabs, Bedouins, Rif Corsairs, Russian Cossacks, Roosevelt’s Rough Riders and American Cowboys Buffalo Bill, the maestro of mounted marksmanship, with his wonderful shooting drills from horseback America, in the time of the first pioneers The Deadwood Stage during a robbery Attack of the Indians Famous cowboys and cowgirls Attack on a settler cabin A group of Japanese “samurai,” with old and modern fighting drills Mexican peasants and vaqueros South American gauchos Cuban patriots 100 brave Redskins The Wild West’s most unbelievable event and the Battle of Little Big Horn or Custer’s Last Stand The performances happen on time and in their entirety in the grand arena Special lighting to ensure a great view The show happens no matter the weather Only one ticket is necessary to witness the entire show as advertised. Buffalo Bill ticket prices at the fairgrounds Standing room only 2 crowns Numbered seating 4 crowns Reserved seating 5 crowns Luxury seating 8 crowns Children under 10 pay half price Advanced ticked for reserves and luxury seating can be bought from 9 o’clock on the day of the show at Istvan Pekker Jr.’s pharmacy (No. 11 Main Square) Szatmárnemeti, July 21 Kolomea, July 23 |

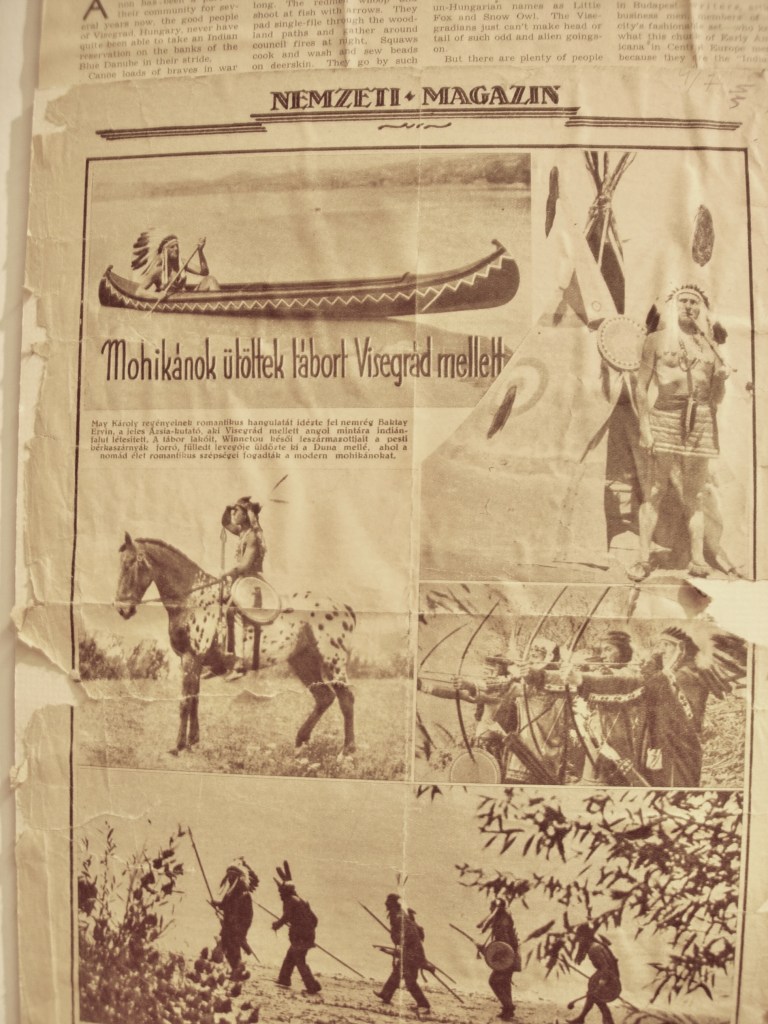

Subscribers reacted instantly to the exotic illustrations and exhortations to action and honor. Some readers may have recalled translations of James Fenimore Cooper, dispatches of the Gold Rush and Indian Wars, Karl May’s Winnetou romances that first appeared in 1892, drawn from Buffalo Bill dime novels and the Wild West’s first tour of Germany in the summer of 1891. Unique American legends already were currency in marketing and diplomacy by the time of this tale from 1906.

The picture of progress, civilization and defense of the settler hearth and home chimed with audiences along the route, themselves a surprising kaleidoscope of people – Bessarabian, Galician, Hungarian, Romani, Silesian, Serbian – and faiths – Baptist, Bektashi, Catholic, Jewish, Lutheran or Orthodox. In the weeks after the fanfare and pageantry, their eyes dazzled by brass and ears numbed by gunplay, more notices for departure from Odessa or Trieste brightly invited this pastoral country of oxen and creaking water mills to join.

Less than a year later, on April 7, 1907, the first film would be screened in Sighet, and the modern age would arrive on the heels of its celebrity friends, modern warfare and genocide, a message that innocuously tagged along with the show, an insidious merge of martial and racial superiority packaged as light entertainment, a familiar contemporary strategy.

There wasn’t time to translate the materials in full, and I asked to photograph the portfolio on the steps of Palace Astra. I’d struck historical gold.

Well, sort of.

Where was my fantasy barn stuffed with posters, dusty plates from the likes of photographers Kabat, Matscho or Ostobolovic, reels of grainy moving image of Bill and Show Indians chasing a giant ball around an arena, even an entire European family of distant Cody or Show Indian relatives?

It was confirmation that the tour wasn’t a hallucination, and I was truly feeling the need to catch up with ciorba and beer across the street to celebrate.

Echim chimed in, interrupting my reverie. “Of course, you could have gone to the Hungarian National Archive in Budapest, they’d have it all digitized.”

Echim was missing the point.

Like a cloud that searches for rain, I wanted to gather the artefacts of the Bill’s last Wild West tour on Europe in situ and to follow the Habsburg route from Trieste to its capital Vienna, then onward to the outposts of Eastern European empire: Budapest, Belgrade, Brasov and Lyiv and the points between, places that weren’t that far apart on a prime rail network that at its best took five hours to reach from Budapest to Sighet, and now took a day. The sole movement here was in human slaves and tobacco brought across the river from Ukraine into what, believe it or not, was a cul-de-sac of the European Union.

All I needed was a doppelganger to help plot the route for witnesses, legacies and ephemerae of America’s first cowboy ambassador, riveting and even tragic, sowing the seeds of European upheaval to come.

Bohemian Rhapsody

Bill restarts in Europe

Bill plans to dump his cramped apartment and buy a new one. He needs space, room, light and air. As impresario, he’s got to squeeze in ideas, performers and beasts, and they all need a place to sleep and park. Maneuvering the rodeo requires skill and resources. He’s wasted four months of the winter off-season practicing for a stunt of size, elegance and price that meets his criteria before he’ll relinquish any funds for a production. The move is calculated by the margin of the air passing through the gaps in his teeth, but the search just goes on and on. Nothing’s right.

He’s pedaled up and down the flat districts of the city with a classified gazette, map and a phone card, earning the scorn of the estate agents for not being hip to a mobile phone, essential for clinching the deal he’s hunting. What do they expect from an antediluvian guy prematurely grey, tossing his flowing locks over the shoulders of his corduroy waistcoat? It cuts both ways as he mocks their indifference and unprofessionalism. Unfortunately, they’re the gatekeepers, and it’s hard to get directly to the owners. It’s not the first time he’s encountered officious people out of their depth, and it’s been one hell of a time.

Bill locks his crummy bike and studies the latest estate agent.

Claudia flows from her petroleum blue Opel Astra, hikes up her crochet dress and lifts herself from the rusty cockpit. She’s got potential. She’s panting, as if she might have hoisted herself from the tanning bed, both her globular breasts rolling from the bra she has chosen as outer wear on this brisk morning.

He’s impressed and not until shaking his beaten hand does Claudia claim the value-for-money search is over.

Her bronze skin smells like the ordure of a solarium or a bum. She raises her hammy arms above her cheeks, her hoop earrings and double chin shake and jiggle, and she’s almost appealing, her bosom heaving from the effort of keeping her body going as she totters into the lift and leads the way to the flat that is going to be his. She already knows it.

He don’t.

The selling point is that it is divided into two flats as he chomps down on the price later, carefully ratcheting down Claudia’s offer as she speaks in her flat poker tone resonating from her rippling throat pinning her phone to her shoulder. There are birds chirping in the audio. Her heels are clacking over terracotta. She could be on a terrace or in pet store naked as she hears his offer for an upscale bit of the ghetto. She’s a bit stunned by the offer, but he indicates that he wants to play poker.

The happiest weeks of Bill’s life are those days living among the boxes. The ceiling is cavernous, and the layout is grand. From each of the four rooms that are the living quarters, he can see the peaks that define the shape of the indescribable city cleft by the great brown river. This is the place he should have landed in since the beginning of his exile, but it took years of wandering to find himself in the right circumstance to make the purchase. A horse or three would fit in the grandiose elevator.

One evening Bill hosts a group of hard-thinking, high-strung European women capable of emasculating a man in a breath. He vows to shut the door so they won’t bother him. Despite his best intentions he showers and shaves, changes into his kaftan and imagines asking any of them to come to his bed if they would have a hankering. He’s already cooked them steak, rabbit and kidney pie, and they’ve eaten the mashed potatoes and quaffed from the bottles of wine rattling in plastic sacks that he inserted in the new fridge that seals hermetically with a sucking sound.

A French gal is pontificating on the futon. She’s a natural ideal of energy quickly inserted into his routine, about how she will work, how her projects are, what they mean. It’s a lot of me. Which one is she? He’s certainly not explaining his own business or detailing how he manages to pony up and pay all the bills.

Somewhere among the massif of books piled on the floor are nuggets of medicine that have come either from a generic plastic bag or from the pewter tea pot. He doesn’t know what to do with the excess of flowers. Bill thought his habit would be another way to initiate the new apartment, but it’s not really working, certainly not with a girlfriend, at least he thinks she’s his girlfriend, with whom he has been bickering all day about money and their excursion in the Alps, and another one scheduled for October in America where he plans to drive her around in his pickup with one arm on the wheel, another around her waist and another hanging out the door.

“There’s a price for everything,” she says, and he glumly nods.

How did she choose the most expensive part of Europe for a holiday after draining the account? What’s wrong with the new fort?

These girls certainly had traditional values.

He did insist on the 400-buckaroo boots to feel comfortable. Bill’s not a mule and his feet are going to glide across Alta-Adige. He doesn’t mull over the faulty logic and masochism of the idea – new boots plus hiking equals yikes! – but he does realize he wants truffles shaved on fresh pasta and smoked, fennel sausages at any altitude.

She’s got a new haircut for the occasion, the thick brown stuff shaved over one eye and behind one ear. She’s looking and listening to him kvetch in the only armchair.

“I’d rather get a drill and make some order,” Bill says.

“It’s not happening with your biking, frisbeeing and stunts soaking up all your time,” she says. “You’ve been up in the hills riding almost every afternoon like a dumb boy.”

She’s triumphant and stabs him in the gut with her toe.

True enough, her marionette, he zips up and down the imaginary wires that cut through the forest, and he follows them higgledy-piggledy, then dropping back into the city, most probably spent for the day if it were not for the sand and grief in his eyes.

He acts deliberately at the prelude to Kali’s two-night birthday bash. He has four shots of vodka before arriving and brings the rest with him. He begins with the schnapps and water to moderate the perception of a buzz. He ignores the wine, beer and pastis until he’s ready to soak up the booze with garlicky Romanian distortions of taramasalata and baba ganoush.

Bill squeezes among his girlfriend’s friends and situates himself among the faces, legs and breasts. Nice there close by Kali. His girlfriend is looking piqued and isn’t feeling well.

They laugh all weekend about her not feeling well every ten minutes.

“Funny,” he says as her diagnosis changes from cramps to eczema to gingivitis.

He can’t do anything but gleefully sympathize after hearing so many complaints in so little time.

Bill’d sleep with any of the girls in a flash if he were his own man. But he’s not, and it’s not going to happen unless she’s involved, which is mostly likely a no-go area. He’s not engineering it either: Do you like your friend? Don’t you want her? Don’t you think she’d like you, too?

He’s been looking these girls over, the ones that he can touch and talk to on the sofa at the party. He’s not crass, wandering from table to table asking, “Are you straight?” culling three partners a week like a troll loitering by a bridge. And he’s not doing anything special when he gazes into Kali’s cleavage as she poses on her knees over his thighs. He cannot imagine fulfilling the temple priestess, more than equal to him in bulk and body, at this little closed gathering of female friends.

“I’m from a woman, too,” he jokes, properly bold now when he rubs Kali’s box through her trousers, and she rightly stings his face with her hot hand.

Bill does not have thirty centimeters of dong and liters of cum at his disposal.

At the public party on the second night, she’s danced glass into her feet and shagged her way from table to table, drop by drop drunker, ornerier, louder and hornier.

Bill is among the first guests though his head is guillotined by the schnapps.

Kali’s got a bent nose, a flower dress and a fistful of flowers for her birthday. He hasn’t requested that she take off her underwear, but she certainly is rubbing something silky under his chin. Seeing that he’s recovering from the schnapps and sober, he’s not at a point where he can react.

The Armenian accordionist is in a foul temper and the Romani musicians are not playing. They’re sitting in a corner, keeping a collective eye on their women. They want money to play and no one’s surrendering a cent.

The venue’s owners don’t have a permit, and they don’t want to pay either. Typical of hospitality, they’re always looking for an explanation of why business is the way it is. The great brown river is low. The clientele is not drinking. The night is one degree off ideal. The moonlight is too strong. The beer is slightly sour. The wine is too warm. The wind is blowing too hard for the disk to cross the island.

Bill shivers in his wood and iron chair. This wasn’t what he signed up for. Mr. Potato is blinking behind his rimless glasses and licking together a date with Mary Jane. The drug and bicycle messengers are coagulating around some videos and a resistance machine that hums through the plywood of the stage decorated with pillows erected against one fence of the island garden. Scene chicks (not nearly as titillating as the day-to-day street chicks) are pulling on their cardigans and adjusting the chopsticks in their hair and going to the toilet in pairs.

The soil is red like a tennis court and the ball of conversation is serving and volleying from mouth to mouth. People are firing requests for beer, cigarettes and grilled, blackened fat.

Kali is shouting and pushing in her dom way, pulling the unwilling to her U-shaped table where the lights are dark, and a trio of women talk in the deep octaves of modern peasant cosmopolitans. None of them drive but they can all hitch a horse. Wrongly or rightly, they believe they will be escorted in the world until their escorts die from alcoholism or angina; then they will never leave their flats except to buy a new radio, new teeth or a new plant.

It’s been a long night of silence for Bill. He can only reflect on his hangover. He’s not pulling Bataille from his blazer pocket and touching his flavor-saver. He’s not screening his documentary on graffiti. He’s not a visual anthropologist but he’s still fascinated by the four walls of the garden that contain the words and gestures of socializing humans.

Days later, Bill squats in the sand on Mosquito Island. The great brown river is mewing against the bank. It’s turgid and almost too frightening to swim in. Even here, mid-route, the water is a mess. There are a few oily clam shells and some pebbles corralled at the edge.

He doesn’t open his eyes under water. He wades in and it’s raining. Bill decamps to the Lake Pub and enjoys a small beer and a coffee to avoid getting any wetter. He looks into the brown eyes of his girlfriend, who is looking relaxed and beautiful. He doesn’t remember bringing her. A mystery himself, he’s trying to decode the crowd of headbangers, fisherman, Roma and yuppies reflected in her brown eyes.

The shower relents and they’re soon playing on the wet sand, throwing a disk between them. She’s hardly any good, and she objects when Bill voices his obscene thoughts, telling her to flick her wrist like it’s a good day in bed.

“What!” he says, defensive and unfurling a litany of proposals. “I’m not piling logs on a fire and forcing you to jump after smoking a joint made from newspaper and bark. I’m not arriving with a case of beer, a cooler, tent, fishing cap and deck chair. I’m not camping on the beach for weeks with you as my wife and progeny. I’m not bivouacking with a group of friends from school, sorting out who’s going to screw you. I’m not sleeping with your students. I’m not having a make-out session with a group of other couples spooned together under the willows. I’m not carving up the mud with my motorcycle. Now, just throw the disk!”

Bill doesn’t have to try too hard to send a forehand or backhand. Catching it is the problem. Especially when it arrives with no spin and a weak trajectory and collapses into the sand like a wet dead fish. He’s pleasantly surprised by her growing backside in her swirl-pattern bikini, especially when she moves enough that it might be considered running. It doesn’t surprise him when he’s got his tongue buried in her hell hole.

Some guys lock up their dog in a shack and leave the CD player on repeat and Bill dances a bit to abstract Ethno as the sun goes down and the chill rises from the wet sand. He does not wade in past his waist, exit, then run and cartwheel or backflip into the water – even if he’d like to since it’s the right time of summer yet minus the right degree of heat and suffering that would make it mandatory.

No one is crashing into Bill’s fire, earrings and Mohawk pressed into the grey peppery sand. No one is dabbing bits of paper on their tongues and calculating if they are beginning to “feel it” while ploughing through booze, resin and peaches they have brought for the night. No one is running down the beach with a brand in his hand like a headlight. No one is maniacally laughing up to his neck in watery sand. No one is swinging over the river from star to star.

No, it’s cold and summer and he’s prone to the great brown river, beads of silver and green foliage smashed along the shore, flowing into the approaches of the great brown city downstream.

Scout’s Rest

Bill’s ranch in Nebraska

Bill Cody avoids where he’s going before he gets there. Bankruptcy – moral and otherwise – is too familiar and unpleasant to dwell upon. The discomfort grows to the point that he considers a pause for some company, but the only pull aside with any guarantee of female candy under the age of 70 is back at the state line in Henry. He’s not edging back an hour just to watch a saggy bottom cancan and flying boobs to sip a bourbon and coke. Still, he recognizes he needs some solace for his violent frustrated memories as he skirts the Sand Hills, dogging along the Platte, wanting to veer towards Colorada for a toke even if he’s firmly stuck in Wyobraska.

He follows the yellow flags pointing south to Cabela’s, and he recalls the mercantile’s bargain cave was a heaven of merino socks. He’d rather avoid the discomfort of bearing north to Pine Ridge to be scolded by the children of Black Elk and the other Show Indians.

He parks and lines up with herds of Bubbas dismounting from their oxen, wagons and vehicles.

Inside the warehouse, partly deaf from a lifetime of gunplay, he picks out a pair of great horned owls’ hua-hua-hua on Cabela’s in-store soundtrack, calling deeply to one another from a dark, harvested beanfield, making friends. Judging from the dudes sighting rifles from the cabinets of weaponry in the gun library, he ought to spring behind the dioramas of cinnamon-maned elk, bobcats, grizzlies and bighorns, and hide along with every tasty specimen of prairie and mountain critter in this temple to hunting, every accessory known to killing animals within its thin metal walls.

Bill’s so nervous he’s about to dip behind the aquariums stocked with bass, catfish, pike, walleyes and scarpies. If that fails, then camouflage himself within the bad tailoring, conservative browns and relaxed fit of the clientele among the field butchery supplies. Then he spies what he didn’t know he was looking for.

Big Buck Hunter Pro.

A few quarters later he’s well above Laphan Cedarburg in 61st and skipping past Carmen Rodriguez in seventh in the top scores, navigating with his brilliant marksmanship towards number one, sufficiently skilled at shooting to know he’s recovered from his sour mood, a taste of the glory of yore like a trail of bled out buffalo, their juice leaking into the carpet, fire retardant for the petroleum industry, not to be squandered on prairie floor.

His name glows in pixels in the video game cabin by the time he limps outside, his shoulder sore, his eyes dazzling, the prairie sweet and real from passing rain.

Bill scoots down I-80, ignoring the signage for cabins at Lake McNaughty, sometimes site of his season tour afterparties and out-of-hand staff retreats. He passes thousands of crop circles, the corn as tall as cavalry, till he makes the hairpin and loops over the dancing banks and islets of the river, cuts through 10 blocks of residential housing, cruises past the gothic Pawnee Hotel for vagabonds where he’s ended up a few nights himself in a long, fun, tortuous life, and humps over the railyards till he recognizes what fragments are left of his home in the surrounding neighborhood of farms and trailers, rodeo stands, the ranch just past the Scout and Lodgepole Motels, sprawling places with thin walls and whores.

His home is a state park now, and he lingers by the rebuilt cow barn that burned down one night when he was touring in 1904. He’s just another face to the guide, no one special, maybe chiseled more than most. And without the goatee, locks and hat, and unaged, who’s to tell him from the local impersonator, Bruce, available for a fee on 530-0990 or 530-3509?

Aric unravels all the trivia in the sprawling wooden house. He repeats all he’s learned, “Scout’s Rest was owned by Pawnee Bill after collecting Bill’s debts, until Orvil Kuhlman, whose son is Ernie, our current neighbor, purchased the house. It was his up until 1960, when the state of Nebraska bought it.”

Bill drags himself past the cob house, spring house and icehouse just outside, nods at the hands’ bunks and recalls the separate bedrooms all too well, as if Louisa were chasing him away with scissors and threatening to desiccate his balls again.

He can’t help but be skeptical about a simulacrum of kitsch, schlock and time plus celebrity, where a narrative about him is sliding around, changing, stabilizing around sites, and then manipulated and sold as photographs and merchandise, hats, hot sauce, toy drums, cap guns, buck knives, post cards, silk screens, posters, dioramas, pronouncements and artifacts that have been saved and reproduced.

Okay, he admits he encouraged it, and he needed the money from signing away his image and copyright. He laughs for a spell until a hiccup interrupts his reverie.

Bill willingly was reproduced as manikin, statue, billboard and town mascot and functions still as a dime to the North Platte economy. He egged them on of course when he put on the ceremonials of the Indian, when his identity of prairie, page and stage collided with comic books detailing exploits he’d never done, the epic of aboriginal versus newcomer, the sites of which are marked along the highway of this strange watery grassland of Nebraska, of creeks, lakes and reservoirs segueing into the arid high country adjoining the Rockies, a last breath at Wyoming’s Independence Rock.

Most don’t bother coming to the house. They just stop at the Trading Post along I-80 and stare at 20,000 balsam wood miniatures whittled by Ernie and Virginia Palmqvist. Drop in 50 cents and the diorama quakes to life in all its magnificent, ordered chaos conjured up under electric lighting: five cent balls and shots for games, calf wrestling, teepee raising and travois dragging, spear throwing, war dancing, drumming, lassoing, bull fighting, trick shooting, bronc riding, horseshoeing, saddling, magicking, juggling and fire eating.

Good value for a helluva good time.

“I was a goddamn genius,” he concludes as the balsam figures come to a rest, among them so many he recognizes and wants to talk to again.

As guide, courier and showman, Bill of that day and hour quenched the thirst of a civilized public in the East and suffering settlers out West. Both audiences wanted romance and adventure, an easy win-win hero. Only he could tame what could not be tamed until the dénouement of the Civil War, addressing the trauma of E Pluribus Unum, answering the wish for glory, a bandage on a public memory of atrocity and starvation long before widespread photography. When hearsay was the same as truth, or near to it, memory made of fragile words prone to lambast and exaggeration in print. When wonder and curiosity were found in the division between that the world that was made and the world that was given. Where story and the cracks in the world at dawn and dusk made knowledge. And there was enterprise in capturing this tension, especially when sold to metropolises like Chicago, St. Louis and New York, to the middle ground, places in between that offered neither urban nor wild adventure, or faraway lands like Paris, Vienna, Munich and Glasgow.

Would it be the flat, golden prairie out the window? Oh, it was flat and full of surprises – anything that moved was a surprise when a man was left to his own lonely devices, so if he could manufacture something out of the grasshoppers, drought and tough conditions, once the Sioux and other tribes were conveniently eradicated, to make him prosper, some myth or mystique that would linger in the collective consciousness that could be packaged, managed and sold, the raw ingredients of a predatory capitalism, then it was suddenly way more than mere grass and brush, flowing to deserts south and tundra north. Indeed it was a factory of legends, as powerful as the sea, on which to implant one’s feet, and certainly having escaped the tyranny of the feudal villages of Europe, the promise of empty land would bring them to enterprise and mostly fail, still in fact servants to interests more powerful than them (beef, railroads, mining), and thirsty for something or someone who would make them feel comfort that their lives had been worthy if not heroic.

Bill and his enablers understood this, and the entertainers that followed – people wanted to believe in something they weren’t – a dream essential to the American psyche of social mobility and personal enterprise. His ranch house, a wooden equal of the brownstones, the grand style and entertainment, the unattainable made real, at least its veneer, the showmanship a cover for boozing, womanizing, and what’s under that – an inferiority complex and probable depression.

No, these are not irrational presuppositions but an intuition into this over-lauded character. Imagine Cody now as an imposter trying to live up to, or authenticate, that myth, when all that is left is dry ground split by the highway and dotted in places with franchises that have nothing to do with local other than paying tax, if that, communities emptied by time, circumstance, a lack of opportunities and held together by agricultural subsidies and little else, at least economically.

Even if all the Buffalo Bill Cody-s convened together, they would be powerless to roll back time like Elvis (or any of tired star of the past). Cody is just an avatar for which, through which some live their desires, especially if they’re losers or failures already (and how are the winners then?), shaking hands and greeting at the Christmas ball (annually at the ranch, a Christmas tree in every room).

Cody hates Scout’s Rest and all the loss it stands for: the marriage, the children, the tours and the fame, the constant restarts for which he can only blame himself. He stomps to his truck and peels away, heading into the Sand Hills and the solace of the grass ocean.

Pity now is an age without need for heroes.

Europe Bison, America Buffalo

Bill reclaims the Fourth in Szeged

The car park was full in Szeged on July Fourth. The parade ground too. The sticky murmur of the crowd rose through the dust kicked by the wind. Few Indians of any stripe had made it to Hungary’s southern city of paprika and sausage since 1906. On this centennial, it was no other than Buffalo Bill and his troupe of irregulars. They’d entertain the townies enticed by colorful posters and bold handbills, drawn to the promise of danger.

Bill was the most famous of Americans, so the media said, the messages deftly crafted by show’s publicity office in advance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild East. They didn’t mention that he was 160 years old. That he was an industry. That he was washed up.

His manager had trouble explaining the idea of the Wild East in his posts. What to expect? Mafiosi, strippers, fast cars and new rich? Ned’s performers looked more like degenerates whom he’d managed to sweep up from the dustbin of history. They were less than noble savages. What did Buffalo Bill have to do with such hard times and mismanagement?

Ned said it was branding: Disneyland Paris owned the rights to the Wild West but not to Buffalo Bill. It was a stroke of genius that he’d managed to get Buffalo to sign up, as the Wild East was on the cusp of failure.

Bill, like his glass of whisky, couldn’t know that.

The star didn’t even bother to inspect the show on the day he signed. He assumed that it was fine.

From his trailer, Bill squinted through a spyglass at the stands on a torrid July Fourth and watched the kiosks. A hot enthusiastic sun beat on the grandstand, sparing the luminaries in the shade. He concluded they must be doing a roaring trade in Stetsons across the way, judging from the dun disks skating under the sun. The electric lights dipped in streams above the crowd who, refreshed with beer and popcorn stamped with the Buffalo Bill name, didn’t object to the heat, even at this late hour. The show was about to commence.

He smiled grimly. Dazed, drowsy, he wondered in all those years if the salami factory still operated in Szeged. He’d enjoyed seeing how the Hungarians rodeoed the pigs decades ago. He was back for one last farewell never to return. So he figured.

Bill knew that he was an incorrigible soak. After cups of afternoon fire water, he’d awoken far too late and missed the troupe barbecue – and the parade that led through Szeged to the arena and drew in the crowd. It was a shame on such a sterling, patriotic occasion that his habits got the better of him. But the roustabouts and performers were reliable, and Ned knew better than to wake Bill from his petulant slumbers. His hunch that there’d be more grub later after the fireworks was not misguided. The show never, ever lacked for a spread. Ned made sure of that. It was in everyone’s rider, just one of many fillips to instill the performers with loyalty.

The crew had unloaded and put up the tents.

“How hard everyone works!” he exclaimed to Szeged’s mayor, here for the preliminaries.

Now they called it edutainment, and the new show was cause for the mayor to linger and study the lessons in how the Wild East was won, if not by genocide or war then by the Yankee dollar. He wondered if Buffalo had found any room for improvement. The East had been stubborn and refused to bow, though many people had tried.

With the ease of a veteran, Bill didn’t need much time. He had his lines and cues down pat. The show had changed little, even after all these years. He wiped the lipstick from his face. He retrieved his wig, wedged in the couch, tidied it and dashed it upon his head. He combed his moustache and goatee. He’d never squeezed out of his leggings from the previous night. He had only to toss on his buckskin jacket in the way of costume and buckle up his guns. Unsteady on his feet, he wasn’t sure how he was going to manage to peg the glass balls on this evening, heat unrelenting and humid too, something that didn’t agree with his crusty body. It wasn’t what he called good riding weather. He fastened his cravat to keep the dust around his neck at a minimum, flicked his hair over his collar. Just like olden days, he hated baths and preferred a bucket. He sincerely hoped his mount didn’t feel as rotten as he did.

He studied himself in the mirror and laughed at the idea of being here again. He didn’t look exactly like Bill but that didn’t stop people from thinking it was him. Shoot, it barely stopped him. The problem was that Buffalo Bill’s personality was so strong it tended to take him over and he began to believe that he really, truly was Buffalo.

Even in retirement, with no more than a Stetson, a pair of boots and a well-trimmed beard to signal any kind of flashy rodeo dressing to indicate he lived the role.

Fans would stop him in the street and ask, “Bison Bill, huh?”

“Buffalo,” he’d correct them.

Sometimes he liked to josh, “Nope, Bison Bill, like you said. Not to be confused.” He smiled handsomely, tipped his hat.

He guessed it was his pickup, a gas-guzzling beast utterly uncommon in the East.

The fame soured him to the possibility of who he was. The doppelganger, the Buffalo Bill who was supposedly dead, had lived on as a legend. Being buried on Lookout Mountain was no obstacle to an ambitious man, his body refrigerated until the road was clear to the foothills outside Denver, mourned at his grave by six lovers and one wife. He tended to take over anyone who was willing to step into his cold boots. Then came all the bad habits, flaws and orneriness.

“The original celebrity,” some people said. That’s why he’d quit. He’d forgotten who he was, and it wasn’t that grand living as an anachronism, a knight in a world that no longer needed such men.

He had no regrets. Like his namesake, they’d lured him back with the bonanza of a Farewell Tour. It was irresistible, even if he wasn’t the real owner, something he begrudged as only Cody could. They’d milk him for the next decade, he was assured. In a flash of sobriety, he’d taken a magnifying glass to the fine type, about as alarming as tallying all the pay spent on hooch.

“Cowboys are the new Renaissance!” Ned had said, slapping Bill’s buckskin coat. “So long as you can stand, speak and shoot straight, welcome to the Wild East. And if you can’t stand, we’ll strap you on an ATV or the stagecoach,” the impresario added none too prettily. Ned predicted market share beyond a niche of cowboys and Indians in Europe.

Buffalo Bill had returned to show business to regain his own sense of being; he was ambivalent whether he liked that person anyway, whoever he was. Since quitting the show at Disneyland Paris, he’d done very well by his savings. He had lacked for nothing. What masters of illusion they had been!

It had been a long journey when he thought about it, returning to Hungary, returning anywhere. It was a victory. He was rich. He was famous. He lacked for nothing. For some peace, he had moved to Balaton. His expenses were little around the lake, but the place didn’t sit that well off season, emptied of flash and bling. He was sure he was made of something else.

The peasant house he fixed up with a modicum of modern conveniences. For a lark he pitched a tepee in the orchard and there he spent most of the time. He ordered lodge pole pines from Slovakia and bison hides from Poland. He paid a squaw from the mock Indian camp nearby to stitch the skins together and decorate them with the signs of the prairie. He paid her to do the sewing in the nude, such was his sense of humor. She didn’t mind it either. Then he wondered if she was his mother, lost to Hippie counterculture. Like him, had she gone to America to live on the Big Res, too?

It was an idyll under the tepee. Outside, he urinated and defecated on the tent flaps tucked under the rocks of the tepee ring and he didn’t care too much about the odor under his professional code of authenticity. All in all, he was talented and didn’t lack flair; he drawn to nothing fancy like a house and crazy enough to forge stirrups and sheriff’s stars in the name of reenactment. In that way he differed from his predecessor. Even his tour trailer was nothing special. What he needed were booze and women, never far in Central Europe. If he had outlived his widow, he would have sold the dreck at Scout’s Rest.

Unpleasant reminders remained in the Hungarian village where he had grown up in rags. A dude ranch for German tourists. A summer rodeo of pitiable merit. Donkey rides. But the mock Indian camp populated from the 1970s by a bunch of slackers and Hippies who believed themselves to be a lost tribe of Hungarian aboriginals was the most sordid in his mind.

As a masseuse and the lowest sex object in the camp, his mother had raised him in a wigwam waterproofed with tarp. He had grown up like an untouchable and hated every moment of it, or so he thought, except when they were chased into the forest by Hungarian secret police wanting to arrest the Indians for betraying communism’s work ethic. The police weren’t willing to run that hard for their meager salaries but at least the game of resistance took on a shade of consequence.

For that he was grateful. He had decided to become a cowboy in this nest of Indians. If he had his way, he would have lined all those mock Indians in the sights of his love, Lucretia Borgia, and liquidated them. The long, heavy gun felt like history tucked under his chin. Heavy, cold, remorseless justice. No more cheats for chiefs and sluts for squaws and the daily internecine battles thereof. No more second-rate mythology of pretenders.

They were all fuckers. Some of them still were alive pretending to be Indians. It was he who was a quarter Navajo blood. “Thunderbird was your grandpa, a poet,” his mother had said, deluded on drugs he was guessing. She’d never said who his father was. In that environment with that anger, he had learned to be the ultimate of reenactors, Buffalo Bill Thunderbird. He was whoever he wanted to be. That was an American lesson. He could reinvent himself as many times as he liked.

No one suspected that Buffalo was Hungarian in America after a time. A degree in ungulates was useful to his surprise. Once arriving in Saint Louis, he had ignored the restrictions of his visa, secured in the euphoria after the fall of communism, and moved westward. Old enemies were welcome and grudges were paused. He erased his accent and adjusted a cowboy legend he’d pioneered at home with the original: breaking horses, working on stud farms, training quarter horses and when forced to, roping cows. A few times he opted to take other jobs, since it was easy pickings. Driving 300-ton coal trucks at Black Thunder Mine had been okay. He did his best to fit in.

Among jobs and having tired of target practice with his arsenal, he’d find himself looking for something to do, no family in America, or so he had concluded as none of his searches for a grandfather yielded a scrap of information. The mystery of his birth was not forthcoming. Yet he gassed up his pickup, hitched the trailer, loaded his horses and tried the reservations up north, asking for Thunderbird. The people of the first nations had laughed at him, a long-locked, bearded, buckskin-wearing kid who wanted permission to pack in their backcountry too.

“That’s a brand of car, ain’t it, kid?” they said, deflecting the question.

Buffalo Bill’s command of subtlety wasn’t firm enough to know they were insulting him and Navajo, too. He didn’t know that Indian tribes were all about politics and turning the tables on an opponent. He didn’t realize the colonizers were vanquishing their colonizers. The exploiter was being exploited, quite unbeknownst to him. He was far too dense in that way.

It was their suggestion one day as he hung out in a bar near the Res. He had struck a nerve with braves. He had encouraged them, buying rounds of whisky with the embers of money burning a hole in his pocket.

“Buffalo Bill, ain’t yah?” a young man had asked.

He shook his head. “If you say so.”

He wouldn’t say Thunderbird again.

“Rodeo tomorrow in Green River.”

“Going?”

“You betcha. Got all my fingers to hang on. See.”

With that invitation, Buffalo Bill had outdone everyone and baptized himself, making the name stick. He entered the rodeo as Buffalo Bill and won the bronco riding convincingly, mounting the broncos in the chute and hanging on well over the nine seconds required for each ride. He had even shown off, mounting a bronco in the ring with no runner, no chute, drawn his pistols and shot out some of the rodeo lights. That had clinched it. The audience hooted and yelled in appreciation. They’d only heard of what Buffalo Bill could do in his long migration through the American consciousness. He was a champ and he embarked on being the man he was told to be.

Buffalo Bill’s personal assistant rapped on the door of his trailer. He held the reigns to McKinley, his roan, and had brought the box of guns and the wireless microphone for the show’s star.

“No regrets,” Buffalo Bill said to calm himself. He was relieved the memories were interrupted. He pulled his gloves off the table, walked outside and fragilely negotiated the steps to his trailer. The stark brightness of the day had relaxed to an opaque light and arena would soon throw its lights into the darkness.

“You’re mighty fine today, Mr. Cody,” said the youth. “How’s that wireless mic I taped on yah’?”

“Rest of the time, I’m unmighty and unfine, that it?” he quipped.

Bill looked a trim fifty with his golden hair. He didn’t mean to be sore, but he was irascible and irredeemable from the whisky. He might as well add uncouth. The kid sound-checked the channel, the device patched into the small of his back.

Szeged seemed a damn fine chance to feel the glory again. He’d forgotten about that part, the glory, since renouncing showmanship, since even the last show when he’d argued with obdurate Ned. The band was serenading the crowd with the strains of cowboy music, and he mounted his horse. His assistant handed him a Winchester. He slid them into the saddle holster. He had riding to do.

With a kick, he surged forward, and McKinley loped through the camp of trailers and parked trucks carrying his portly load. McKinley smelled the drool of the buffalo, and he smelled the spit of crowd and he dreamed of the flowing gun smoke to come. It didn’t bother him one bit. He headed straight for the group of riders holding flags and they fell in behind Buffalo Bill. They were a well-trained bunch, hardy and tough. It was precise, dangerous work at a fast pace.

First the braves circled in the arena. They rode with grandeur on their white horses and showed their personalities with flare. Then followed US cavalry, Arabs, vaqueros, gauchos, cowboys, lancers, and platoons of Eurasian armies. At least that was what the crowd was told about the drapeau and dressage. The crowd shook at the sight of Mongolians, far too close a sight, invaders worse than Turks. The horsemen circled in ranks of five or more, flags flying, guns and sabers, horses nickering and snorting, the Indians holding their lances and stirring their bonnets in the center, their shields on their backs, their garments fabulous and decoration fabulous, until out came Buffalo Bill.

He heard his cue from the band and jumped right through the banner stretched before him. The musicians puffed away at the brass and winds, the drums rolling in a splendid march. The music then segued to the overture for the grand review. Ned had decided CDs were the next budget reality for the Wild East show.

“The Honorable William Fredrick Cody!” boomed the announcement over the public address system. The crowd had read the program and knew what to expect: a PRESENT that shall in every respect equal if not excel its envied record of the PAST.

Out came a mighty roar from the crowd, waving their hats and their heads in astonishment as if they, the whole town of Szeged, had traveled to the pomp and excitement of a century ago in that very instant when cowboy and old scout rented the fabric and came whooping into the arena.

Buffalo Bill lifted his cap and backed his horse into the ranks of Indians. He stood tall in his saddle. McKinley bowed his head. He announced the performers and contrasted all the acts of the show as his wont. When unable to do this, he would use the Deadwood stagecoach or a buggy, depending on the needs of his health that day. He was genuine and feeling great as he settled backstage with the troupe.

Already the spectators were agitated and loud. These were real Indians. These were not actors. They were the real deal, all right. Everything led them to believe it, though Bill suspected there to be a great deal of make-believe on the part of the Czech management. In the end the fibbing didn’t bother him, but the management did because they didn’t care too much about the origins of the labor, so long as they didn’t cause too much trouble. From afar they couldn’t see the worn costumes or that many of the professed Rough Riders of the World were mostly Slavs and Romani. They didn’t have that kind of operation. It was a knock off. Nonetheless the action was so gripping and fast that no one noticed such a detail that might bother him if he’d shelled out a good chunk of change for a bunch of poseurs. Yet he couldn’t deny anyone could be a cowboy or Indian. It felt too good.

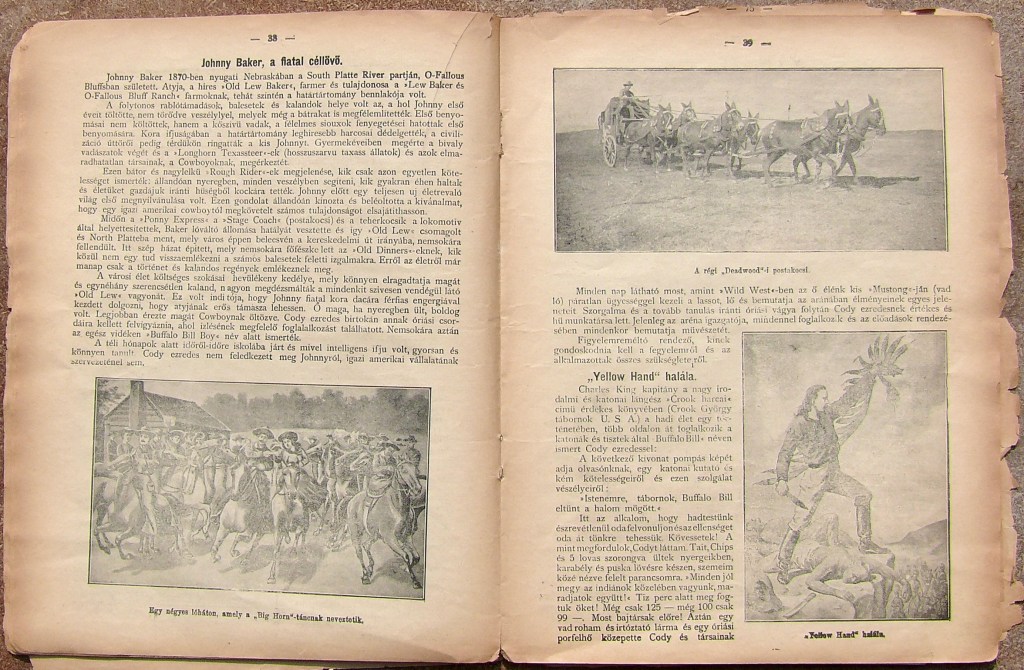

Johnny started with his routine of champion marksmanship. They lofted glass balls into the air, and he shot them reliably from a range of positions. Then came the cowboys and broncos, struggling in the mud or turf, whatever the arena happened to be, the goalposts sometimes not even removed. The cowboys were in a real pickle without a chute but sometimes they did manage to buck across a field, and it made for peals of laughter echoed in the arena because of these men with sullied reputations snubbed the broncos. It hushed once the Deadwood Stage made an entrance, circling the arena, the carrier of such illustrious passengers as kings and queens. The Indians ambushed the coach and hand to hand fighting soon began on it roof. Here, the US cavalry always made it, repelling the Indians and saving the day. A small yellow tarpaulin square was laid, a mock fort was erected on the field and the drill sergeant marched out the Zouaves who had fought in the Indian wars after earning their stripes at Gettysburg. Nothing was without meaning at the show. It was a beautiful spectacle of choreography, the patterns of men whirling and stepping, folding and circling, dancing with guns. Everything was designed to raise or lower the pitch of excitement and artistry. It appealed to the highest emotion and Buffalo always was lured into action from his whisky.

The Indians established camp after a long journey raiding. The women unloaded the drags and pitched camp and the men smoked their pipes and talked about issues of the day. They had no idea that the scout approaching was Buffalo Bill scouting for the US cavalry. The Indians engaged in a medley of shaking and stamping dances to celebrate their raids. They had grown careless. Two white female captives were raped by the warriors with the help of the squaws. The cavalry came in two charges and dispatched the Indians, but not before they killed one of the white captives. Bill felt there was a need for some portent in the show about consequences.

He had told Ned, “Makes it more real, up close, live.”

He often sensed that audiences weren’t all that interested in the narrative to the stunts. Maybe the chance of an accident brought them. Or they wanted to heckle the performers. He was disappointed that peopled didn’t care about improving history.

The show went on. Bill came out to shoot the glass balls lofted into the air. He was man, horse and gun, a centaur, chasing at top speed after the amber balls launched before him. He cheated a little and used shot, but still he was mounted and shooting with both hands, his torso twisting to and fro, his legs gripping McKinley’s back. Then came the lariat-throwing vaqueros and gauchos, followed by whip cracking by Johnny, the Pony Express, a rope race, an Indian dance tableau complete with deer and elk and, last before the finale, the buffalo were unleashed on the arena and hunted and stalked by the hungry braves. The noble beasts stormed away in red light and fog.

The finale, the first scalp for Custer, called for a soaked Bill to duel with Yellowhand and count coup over his corpse. Cody then joined his grazing horse, obtuse to the critical scene, and galloped into the last review. The band whipped up a final number. The music changed from Offenbach to a cowboy song. By now the crowd was exhausted from incredible feats of horsemanship and dexterity. So much had happened in so short a time. Every inch of the arena had expressed the constant fighting, riding, dare-devil life of a swirling frontier. It was spellbinding. The audience clapped repeatedly, and the performers were called out again, the applause for a performance showing so truthfully their heritage and what they really did back home. It was triumph.

Buffalo Bill waited for the crowd to disburse and still on horseback he talked with the local dignitaries at the grandstand. The number of children who wanted to be cowboys and were struggling for an autograph was ludicrous, but Buffalo Bill patiently signed away, used to the platitudes.

“We’re very serious about who we are,” he said to one persistent child anxious to be a cowboy.

He told a concerned parent, a lawyer by the look of it, “To be good, there must be something in the eyes, something clear. You can’t use just your brain. That’s useless.”

The other stars of the show were also busy. Black Elk was surrounded by admirers. Johnny and Annie, too. It seemed like all performers had materialized at this anniversary show in Szeged and the camaraderie warmed his tatterdemalion heart. Then he swore he recognized a few faces among the Indians’ fans, the very same camp fakers who had treated him and his mother so cruelly, and he stormed off to his trailer, infuriated. He never could escape the reminder that he wasn’t Buffalo: what he felt that he felt wasn’t what he felt. That was his dilemma. He was neither completely Buffalo nor completely Bison.

Buffalo Bill dismounted onto the steps. He handed his guns to his personal assistant, and he slipped inside. He stewed on his dilemma while he completed his routine. He polished his decorations and insignia. He fixed a torn glove. He rubbed the dirt of his boots. Until the rich smoky smell of barbeque matched that of the whisky in his glass and reminded him that he was hungry, that he couldn’t soak all night long without food and company. That’s right, tonight there would be something special for the artists: a firework show. How magnanimous: sausages and great cuts of pork on the grill.

Already the roustabouts were unstaking the tents and loading gear from the football pitch. Concessions were packing, too. The animals were groomed, watered and fed. The trucks were being loaded. The music had stopped and just a few lights in the arena were on. The shadows of the artificial lights that hid the obviousness of the tricks reached far across the arena; they seemed to say that what was then and what was now were not the same thing, that covering history within a breath of its occurrence had no cache anymore. People got it from technology anyway, up to the second by now, so much so it didn’t even seem like history.

Buffalo admitted it, warily. This was a step down, a big one. It was a sham. He despaired at the deplorable state of the show. It was a flop, and he was its ringmaster. The old cowboy magic was falling on deaf ears. It was harder than rounding up a few horses and firing bullets and arrows into the air to influence the collective conscience of nations like he had before.

People were given what they wanted to believe, whatever he told them like the best of grifters. He was the linchpin. Everything was as he had witnessed it. Without his word, no one would believe that the drab, poorly dressed performers were anything other than degenerates, best to lynch, for wasn’t it all about blood and race? He closed his eyes to the Czech manager’s abuse of everyone. How many of the increasingly slim artists were left after tonight?

He easily deceived himself. That the great gaping gaps in the arena was full. That the simple, rehearsed acts were fantastic. That the traditions of the West lived on his word alone, certainly, in the cowboy bars of Switzerland, Germany and Czech, but that was about the total of the appreciation for the mystique. In most metropolitan cities, a cowboy was a genre of homosexual riding bareback. He was Atlas, holding up the rugged cowboy world, a flamboyant cowboy queen wearing no more than a skirt. He would have best been left out there, on the frontier.

Yet he was anticipating the next stops of the tour, something special Ned had lined up: Transylvania. He’d heard it was the last wild in Europe and he’d been invited to a bear hunt. He would educate the wilderness.

Unstable Ground, Uneven Water

The Hungarian Indian movement

The escalators lifted me into the gray – a relentless, cold, bitter, snow-washed gray. Neither majestic nor cool but dirty and corrupt. A merciless, unkind, infinitesimal gray that climbed from the ground and stamped down from the sky, that clung along the Danube and pinned thousands of souls to the earth, spat in their faces and poisoned their eyes. No matter if sprayed with revolutionary red or patriotic blue, the relentless gray wiped away history with oppression and hopelessness that only a mix of brandy, tobacco and violence could numb.

I killed time in the cold stench of the underpass, firm that I was part of a cultural collision, here to encounter the shreds of what was left and what it created.

Two Romani musicians cloaked in camel hair coats grumbled at their violins as the trams creaked above us. They took turns smoking near the stairs. I gave up and felt my way through the gray to a nearby jazz club. I wanted to talk to the soul whisperer who trained me how to keep on the straight and narrow.

“Either you get a good horse and a bad instructor or a bad horse with a good instructor,” he said after I’d spilled my guts of things I did or thought.

“Time won’t go backward,” he assured me.