Choices

Cidermakers face hundreds of choices when making cider: when to pick what apples from what sites, how and what to squeeze, and when to bottle for what style. Surprisingly, a sort of structured neglect can do wonders to the process so long as hygiene remains paramount. Along the way from orchard to bottle a lack of time can be the deciding factor, especially for people in an enterprise that is distinctly uncommercial – done out of curiosity, tradition or just for a laugh.

And a laugh it was.

“Let’s pick some apples,” teased Guy, my Kiwi co-conspirator, come mid-September.

I hadn’t played much with what was required for a 2022 edition. The equipment was in disarray, tossed into the cellar for two years, and my calendar was struggling with a hostile employer. For better or worse, I made the call to the source.

“Hello Margaret. We haven’t spoken for a long time, and I was wondering if we could come pick some fruit. Is anyone else lined up?”

“Come and help yourself,” she said sweetly, adamant that no one else would beat us to it.

We turned up later that week with a Ute filled with a dozen empty crates. The riverside orchard, a quadrant of Batheaston’s original market garden, was singing with crop. Already fruit had been shed into the grass, the conclusion of an abundant summer.

Our gear consisted of two ladders and a boat hook. We handpicked the best apples that were in reach, then robustly agitated the branches to knock down the rest, avoiding taking the windfalls tainted by bacteria and bugs. It was guesswork what the trees were: perhaps a pair of tart Blumer Normans, a trio of astringent Dabinett, perhaps a few Cox varietals for sweetness. Our crates filled with the luscious orbs, loosely sorted by variety and condition.

The Ute was divinely aromatic as we reported to our cider barn, no more than a shed in the pretty village of Priston. The apples were unceremoniously stored, safe from autumn rains which would encourage mould and yeast, dramatically affecting sugar and acidity levels.

Mashing and juicing

It was a miracle that space for phase two appeared in mid-October. The apples had been inspected every so often in Priston, those blackening and rotting chucked into two uncovered tubs to ferment naturally or in the local parlance, keeve. What was careless transformed into marvellous.

That weekend start we sourced our equipment, gathered a few wheelbarrows of Priston apples from a shiny hillside orchard and set up our stall.

Equipment

- Two basket presses, 18 and 24 litre, respectively

- Two fruit mashers, one small 20 litre, one 50 litre borrowed from the community barn

- 5 packets Garmin’s cider yeast

- NoRinze disinfectant

- Campden tablets

- 6 25L buckets

- 1 60 litre culinary barrel

- 6-10 demijohns

- Multiple airlocks

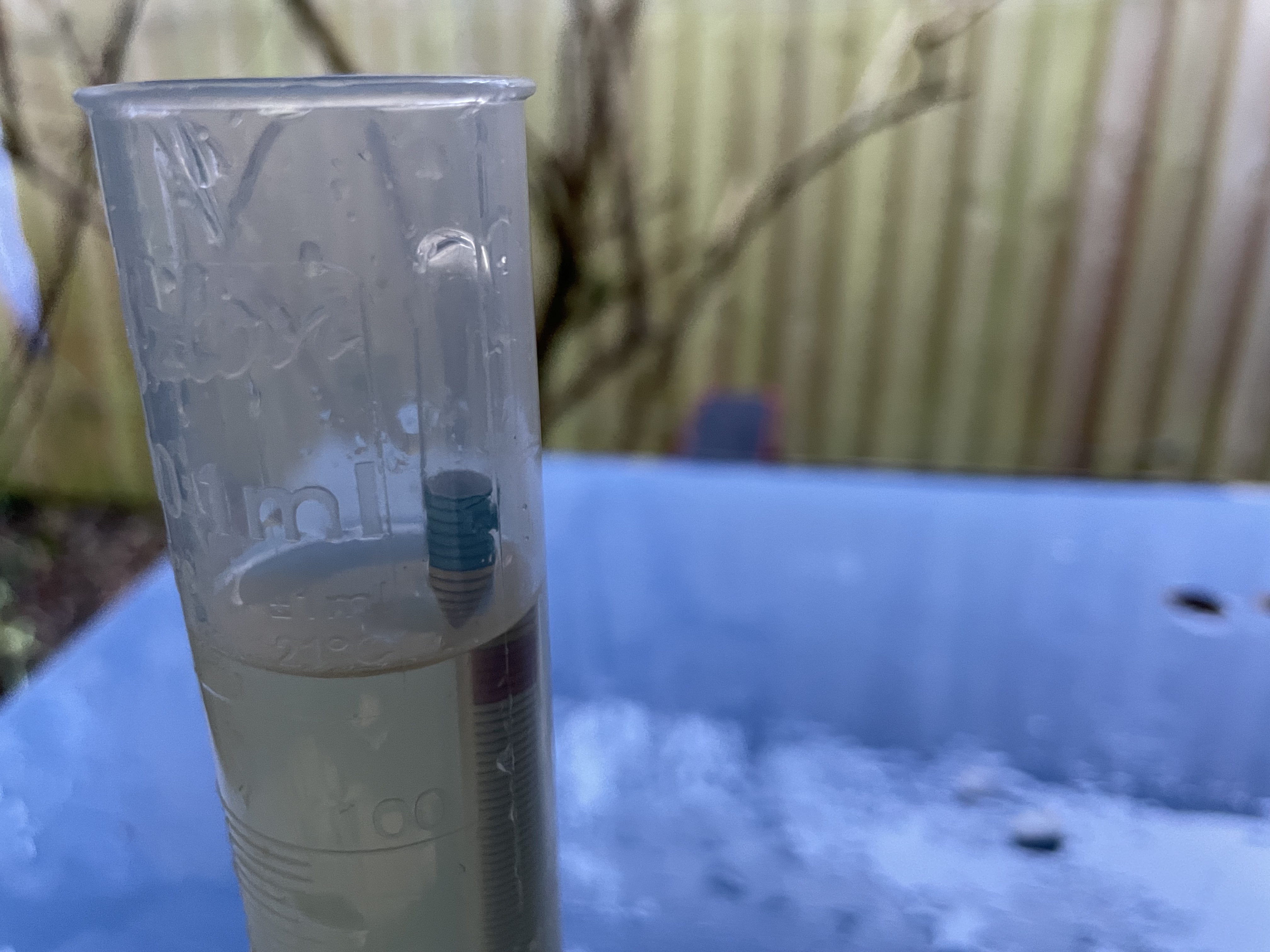

- Graduated cylinder and hydrometer

- One table and an abundance of knives, sponges, buckets, clothes, brushes

- 10 crates apples, approximately 400 kilograms, from which 20 per cent were fermenting in tubs on their skins

- 80 upcycled sparkling wine bottles, 80 cages and plastic corks; 24 screw cap plastic bottles

The weekend sizzled with glorious weather. Waterproof trousers and wellies were enough as I washed and sanitised the equipment. By afternoon the chopping and crushing began in earnest. I checked the manual to assess the crop. Surely we counted on Bulmers Norman, Dabinett, Brown Snout and Stoke Red among the blend of assets.

Guy and I agreed since our last endeavour that we were interested in maceration, meaning we would let the mash soak overnight on the skins to add flavour and to create something less sharp and simple than 2020’s creation, a nervous tart vintage infested with memories of Covid-19.

The big hand-powered crusher made easy work of the task, so we ran the mash once more. A break appeared for a roast pork dinner with our children, then we pushed on till midnight, grinding out wet sweet juicy music.

We crushed the leftovers the next day, then pondered the most interesting decision – what to do with the two tubs of brown and black apples dusted with colonies of wild yeast?

“Crush them!” yelled Guy.

“Let’s hold fire till we finish squeezing,” I said.

If we were to experiment, we had to stay clean.

We loaded the two basket presses with macerated pulp and filled our buckets with red golden juice, breaking off in turns to mash the leftovers.

A sterile environment was maintained as best as can be expected outside, and a few breaks were enforced to entertain village onlookers. As coincidence would have it, you recognised the neighbour.

“You were one of the good writers on the course,” he said, divvying up dried apples and pears to us from his leftover Glastonbury stock.

Nothing about cidermaking or times-gone-by surprised anyone in the least on this glorious day.

Jackdaws scraped the sky, darted in the trees and shouted from the gold cockerel weathervane atop the village church as we pressed: clear free run juice to a caramel toffee fraction. We had to stop ourselves from overdoing it and drawing bitter cyanide oils from the apples’ seeds.

By Sunday afternoon we had exhausted our young helpers – and ourselves. The day was nearly over. Three buckets were sealed and we still had the blackies ahead. Would this apple dream never end?

It nearly did thanks to reckless overenthusiasm for juice when Guy split the cast iron head of the village press, rending it out of order.The blackies ran through the masher like butter, squirting everywhere. They flowed out the basket in a strange cloudy juice of vast quantities, tasting smoky and rich. What was this nectar? What would it do to itself? To us? We awarded this flavourful conundrum two of its own promising buckets.

Mash and juice on October 15-16

| Litres mash | 175 | 75 | 75 |

| Status | macerated | fresh | rotten/keeved |

| Litres juice | 50+ | 22 | 40 [!] |

With one last hurrah, we barrelled 60 litres of pomace for science, adding water and sugar – unfortunately not mash suitable for a still but an amazingly stiff organic vinegar!

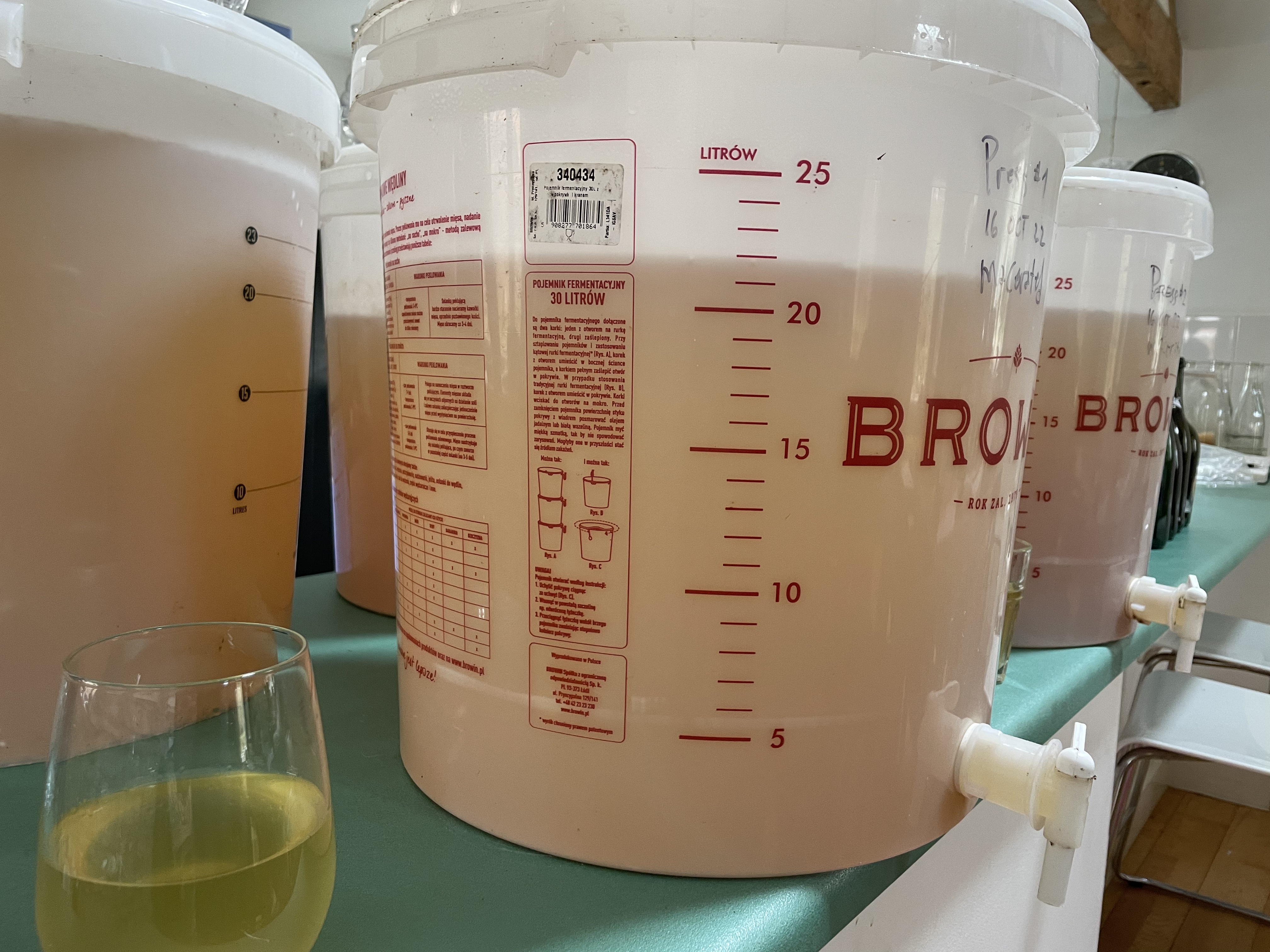

As the rains began, all the buckets were labelled, lifted inside the house, treated with a light dose of disinfecting Campden tablets, sealed and airlocked and left at a coolish 18 degrees Celsius for the fermentation to take hold – only once Guy dashed the juice with cider yeast a few days later.

Assessing and racking

Three weeks into fermentation in the house’s cool temperatures (we had a cost-of-living crisis after all), it was high time to observe what we had achieved in Priston. Guy assured me they had belched carbon dioxide throughout the weeks. A strong scent of alcohol, orchard and yeast greeted us once we cracked the lids. Degrees of gold revealed themselves in each bucket, some with floating lees and others with a light coat of flor. We decanted into assorted cups and measured alcohol levels in our kitchen laboratory. Upon assessing that a pleasant amount of residual sugar remained, a decision was made to halt fermentation and maintain the batches as separate unless we would create faults blending too early.

We then racked and siphoned the cider from bucket to bucket and tossed out the lees. We ran more taste tests, mixed and combined to see if we could even out the inconsistencies, and altogether we were confident that black, bruised fruit was no impediment to good cider, adding body, flavour and complexity.

While still rough and unfinished, it seemed to be a solid result that would condition well, or if we had money to burn, benefit from the vanilla and cloves of a new oak cask. Overall, we were pleased with our off-dry cider. No wonder it was common practice on farms to rest the crop in a cider barn for several weeks to add flavour and, with the use of oak barrels, body and texture. What had been an unconvincing “I sort of like it” two years ago was now a confident, “I definitely like it.”

I wouldn’t see or hear from those buckets again till Christmas six weeks later. Only the occasional report came tfhrough from New Zealand.

Assessment on November 5

| Batch | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Specific gravity | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.06 | 1.15 |

| Mash and juice | macerated | macerated and fresh | macerated and fresh | fresh and kieved | fresh and kieved |

| Remarks | sweeter than expected, cloudy, sunflower | sharper; late start to fermentation | mellow, soft, more tannin | dry, smoky and woody, roaring off to fermentation | sharper and woody; late start to fermentation |

The cider was left unperturbed in the cool house, gravity filtered in the six weeks until December 23 – another now-or-never moment in this sequence of cidermaking – when we would rack again, lose a bucket to waste, blend a little, and properly stop the fermentation. Then we wrestled the four batches to the shed to the shed where the cold would stop any fermentation.

We pressed our leftover pomace experiment into four demijohns of vinegar and then we pressed a tub of pears I’d scrumped from the lane by our children’s school – they also ended up in demijohns for the ultimate experiment.

Blending and bottling

Spring was around the corner in theory, and the batches occupied valuable space, not to mention jeopardy from rats, engineer-minded children and a clumsy Rhodesian Ridgeback. The batches had been shifted inside the house recently, and we were concerned by burping airlocks. . What we hadn’t calculated was that this might be malolactic conversion led by bacteria rather than yeast. This would give a softer, fuller expression and body to our cider once cellared and conditioned, but we didn’t realise that yet.

We agreed that we would blend the batches since they all combined in the glass well, so we poured and stirred as best we could with our limited hardware. We’d prepared with scavenged sparkling wine bottles, sourced cages, plastic corks and dextrose to trigger the second fermentation . We were outside again, everything prepped and cleaned with hot water and NoRinze.

And the job flowed quickly: heaped tablespoon of dextrose, 750 millilitres of cider, cork and cage. Once we ran out of glass, we opted for half-litre plastic screwcaps, ideally portable for a park or a hike. We gave each a squeeze to leave room for the fizz.

We were so good for time we managed to rack and bottle the black label experiment, a vivid parade of glowing browns of which we were terrified – a taste of that high octane brew made us think it could be a splendid coup d’grace on a festival afternoon.

Bottle yield on March 11

| Number | Volume (millilitres) | Packaging | Product |

| 96 | 750 | glass | Cider at 5.5% ABV |

| 24 | 500 | plastic | Cider at 5.5% ABV |

| 6 | 750 | glass | Black label edition at £%^! ABV |

| 8 | 750 | glass | Apple vinegar |

Conditioning, cellaring, tasting

We cleaned equipment, divided the bottles and hailed it a success. The cider was still in its infancy, and a second fermentation, whether successful or not, was ahead – the signs of which appeared very slowly. My share went in crates down in my cellar, without weekly riddling or any fuss, piled next to the other years of experiments.

By May it seemed apt to chill down a few and have a taste. That juice surpassed my wishes: off-day, tangy, earthy, appley, smokey, with a creamy body from malolactic conversion and a slight hazy pétillance. Even my mother liked it – a lot. What’s more, it seemed worthwhile, a combination of resourcefulness, male bonding, and touch-and-go time management, with a beautiful result.

Like a dragon sitting on a treasury, I guard my share jealously and you must qualify as a special friend to convince me to release a bottle. We almost could afford to dream of bigger goals: a proper press, more orchards, a barn, the first stages of a commercial endeavour to make money – even if that might ruin the fun.

If we’re lucky to pick an orchard in 2023, let’s see what two lads can do like countless lads like them faffing about for laughs in the West Country.

Calendar 2022-23

| September 22 | Apple harvest |

| October 15-16 | Mash and press, start fermentation |

| November 5 | Assess juice, rack no 1 |

| December 23 | Rack no 2 |

| March 11 | Blending and bottling |

| June 3 | Conditioned and ready to drink now, suitable for ageing |